About this Article

This article provides a historical tour of Iran’s theater during the past one hundred years. Both the religious and the patriotic themes which loom large in Iran’s popular and folk art are discussed in relation to Iran’s theater. The gravitation toward Western plays and particularly European theater, presented here, reveals another aspect of Iran’s encounter with modernity and the West. Additionally, the history of various forms of training institutions in the field of theater established in Iran is laid out in a chronological format. The influence of social and political events on Iran’s theatre and the directions it had taken is also an important part of the history of theater presented here. The problem of censorship with which Iran’s theater has been grappling is another important topic to which the author devotes several pages explaining the challenges posed for that industry. The author also devotes a large section of this article to introducing the most influential producers, directors, actors and actresses as well as their teachers and mentors of each era. The national and international festivals in which Iranian theatre was presented are also covered in this well-researched article.

Writing a script for and playing in theater, as is done in the West, plays a significant role in awakening the people of Iran to shed light on their basic rights and their realization. One of the clear manifestations of such enlightenment was the role that this type of theater played in starting and fructifying the constitutional revolution of Iran.

Western-style theater, which, from its inception, was purposed towards edification of ethics and enlightenment of thoughts for betterment of life, familiarized people, before constitutionalism, with the disarrays caused by dictatorship.

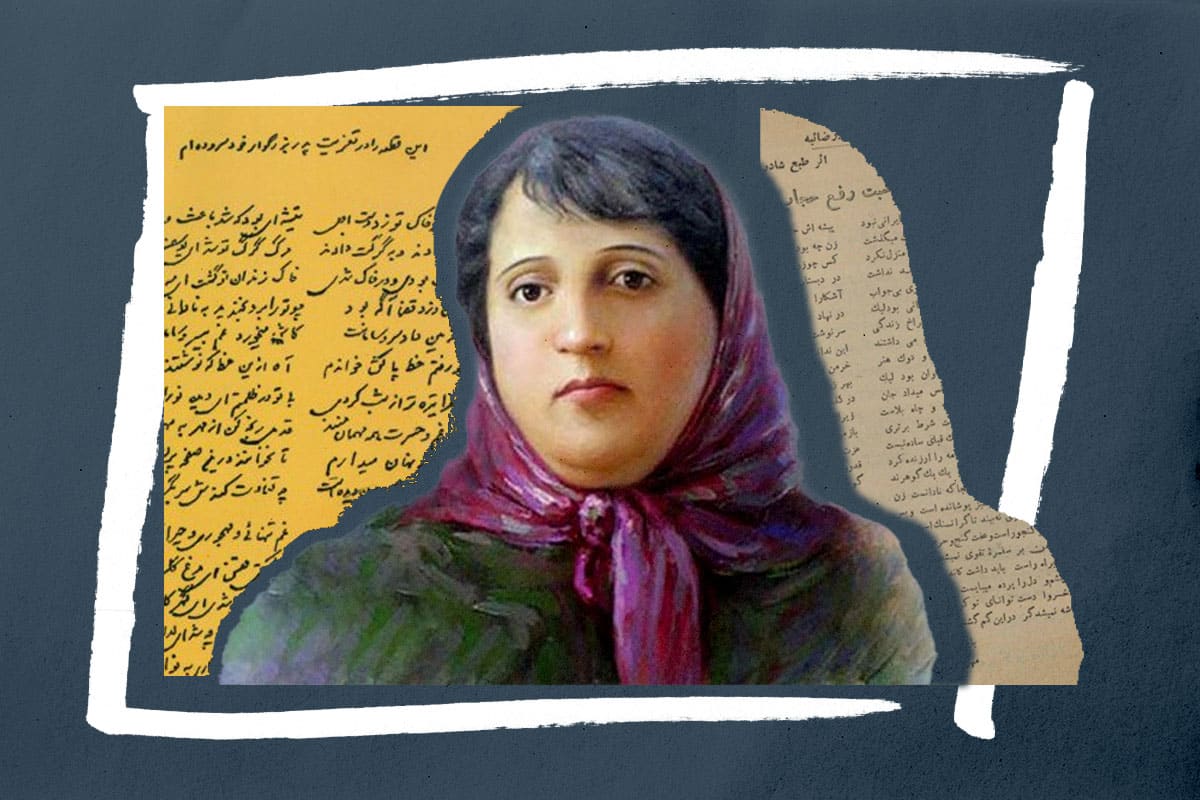

Translation of European plays and writing scripts in Western-style, which found their way to Iran as a result of efforts by Mirza Habib Esfahani, Mirza Fath-Ali Khan Akhundzadeh, and Mirza Aqa Tabrizi, gradually found enthusiastic audiences among modern and cultured Iranians who were interested in the new world civilization. The trend of translation, writing and staging valuable plays, during and after the constitutionalism era, expanded in time and attracted the attention of the masses, especially the young and educated generation. Various cultural and social societies also recognized the propagandistic importance of theater as an effective outlet and started utilizing it to promote their ideologies and political views. Little by little, theater groups emerged and special halls to take plays on stage were acquired.

The first serious theater group that was called “National Theater” was formed by Mohaqeq Al-doleh, and the first hall that belonged to the private sector was the central hall of the Grand Hotel, where plays, operettas and concerts were staged, and movies were shown. Plays staged in the Grand Hotel were initially inspired by operas of Aziz Haji Beigov such as “Leyli and Majnun”, “Kerem and Asli”, and especially his two famous operettas “Arshin Mal Alan” and “Mashhadi Ebad”, which were widely known due to the tours of Caucasia’s theater group to various Iranian cities. Also, because of the tradition of poetry and music in Iran and the passionate interest of Iranians in these two expressions of art, at first most plays were musical, or, as said by Jamshid Malekpur, melodious shows. The most effective of this type of plays was an operetta called, “Resurrection of Iran’s Kings in Madain Ruins”, composed by Mirzadeh Eshqi, who took it to the stage of the Grand Hotel hall in 1882 two years after its performance in Tabriz. In time, this hall changed its name to Tehran Theater, Dehqan Theater, and finally Nasr Theater, with the main purpose of staging western-style theater.

At the beginning of the 14th century AH, the conditions were ripe for production of more social and critical shows and the blossoming of true cultural and artistic plays, but the shows of social and critical nature were suppressed by coming to power of Reza Shah and return to dictatorship. Playwrights had to resort to historic themes, past glories, mythical fables, religious stories, and mystical philosophies. Government affiliated artists and playwrights focused on subjects that indicated the country’s advancements, such as elimination of superstitions, women’s emancipation and entry into social activities, creation of a modern army, and the importance of sacrificing for the country and presented those themes, in one way or another, in their arts. As for the educational shows that were produced and staged by organizations such as the “Institute for Intellectual Development”, the themes were mostly about the damages caused by alcoholic drinks, illegal drugs and gambling, emphasizing education and the merits of being dutiful, honest, and helpful to others. As a result, theatrical activities in Iran did not move forward from the initial state, where thematic designs were concerned. Now, the audiences were mostly those who went to see them for entertainment, pastime, or perhaps to receive some words of wisdom, which could, of course, be another feature of such shows. Even among performers, one could hardly see the joy, enthusiasm, and the sense of commitment to theater as a social duty or even a religious principle as once existed.

Nevertheless, in that period of time, despite the overwhelming suppression, valuable criticisms were written by knowledgeable individuals as a result of further relationships with foreign countries and sending a great number of students to advanced and industrial counties and relative familiarity with global cultures and civilizations. Also, educational courses of performing arts were offered, and there was tremendous qualitative and technical developments and advancements in writing and performing theater by establishment of “Acting School of Art”, where numerous middle-class men and women attended and thereby sowed the seeds of valuable theatrical activities, the cultural fruits of which began to emerge extensively in the days following the summer of 1941.

Education in Europe and its Effect on Iran’s Performing Arts

Students who went to foreign countries to study and research performing arts brought back new ideas with them on how to stage a play. Among them were Seyyed Ali Khan Nasr, Hasan Moqadam, Mehdi Namdar, and Abdol Hossein Noushin in particular, who left his main field of study and primarily focused on performing arts.

Abdol Hossein Noushin was born in a religious family in Mashhad. Upon completion of his elementary education, he moved to Tehran and received his [high school] diploma from Dar-ul-Fonun. In 1928 he went to France with a group of students to study history and geography but ended up attending the conservatory in Toulouse to study theater. As a result, his scholarship was canceled and he had no choice but to return to Iran; however, he set out for France once again, this time at his own expense, to continue his studies in French literature and performing arts. In 1932 he returned to Iran well prepared for more serious involvement in theatrical work. Among Noushin’s brilliant works in those days was taking to stage one of the works of Marcel Pagnol called “Topaze” (People) and appearing as its main character, which truly showed his theatrical talent.

Parallel with a trend towards modernism and increased connections with the elite of other countries in those years, Vahram Papazian, a well-known soviet actor of Armenian descent, was invited to Iran to appear in several plays including Othello. The collaboration of Iranian artists with Papazian had a great positive impact on Iran’s theater when Iranian actors learned for the first time of an international actor and director’s working style.

At the same time, while other artistic activities continued, Iranian cultural officials, under the supervision of Mohammad Ali Forughi, began preparations for Ferdowsi’s millennial celebrations. The celebrations were held in an air of magnificent glory in 1934 with the participation of the most notable scholars of the East and the West, and parallel with various seminars, several plays on the themes of Shahnameh were also staged. Moezzodivan Fekri wrote and staged “The Tale of Rostam and Sohrab’s Battle”; Zabihullah Behruz played the role of Ferdowsi in a story he had written by the name of “A Night With Ferdowsi”; Abdol Hossein Noushin, in collaboration with Mohammad Ali Forughi, Mojtaba Minovi and Colonel Minbashian (Head of Music School of Arts) took to stage several tableaus based on stories of “Zal and Rudabeh”, “Rostam and Qobad”, and “Rostam and Tahmineh”, where he (Noushin) played Rostam, and Loreta played Tahmineh and Rudabeh. Noushin’s acting, staging, and directing of these plays, as well as Loreta’s ability to portray the characters assigned to her, caught everyone’s attention. Noushin and Loreta got married the same year and continued their productive artistic collaboration together.

In 1937, Noushin and Loreta, together with their all-time coworker Hosein Kheyrhah, were invited to the Soviet Union to participate in Moscow’s theater festival. Following the festival, Noushin and Loreta set out for France to complete their education in the field of theater.

Despite Reza Shah’s autonomy, one cannot deny that he was highly interested in civilization’s material features and exerted a great deal of effort to promote them. In the field of theater, he made some improvements and ratified some laws, which nobody before him could enforce out of the fear of the mullahs. In the final years of his rule, he took action to build the municipality’s theater house, and although building theater houses and museums were among the major responsibilities of the municipality, the severe objection of some religious radicals led to the elimination of that responsibility from the municipality’s manual. However, Reza Shah ordered the city hall of Tehran to build a hall with every necessary tool to help Iran’s performing arts.

Second World War and Formation of Political Art Groups

With the allies of World War II in Iran and the banishment of Reza Shah, a relatively more open political air permeated the country and translation and staging of valuable foreign theatrical pieces became more relevant. The most brilliant piece that was written and published was Toop-e Lastiki or The Rubber Ball, written by Sadeq Chubak in 1949, which magnificently portrayed the fear and suppression of Reza Shah’s monarchy, but no theatrical group took it to stage.

At that period, cultural and social groups, as well as political parties, found a new spirit and prepared the young people to go on stage by setting up shows and holding training courses. Some political parties even took advantage of the young population’s interest in theater and set forth the condition of membership in their respective parties for registration in training courses which were conducted by famous and respected artists[3]. What happened next was the formation of many theatrical groups who took to stage numerous valuable pieces with better quality than before in theater halls that were made for that purpose. Producers and directors of these shows, who had been trained and educated in Iran or overseas and knew how to best stage a theatrical piece, trained their actors before assigning a role to them and prepared them for this significant work. Most trainings offered to actors were about speaking techniques and stage presence. These trainings usually involved two different ideologies. Actors such as Abdol Hossein Noushin and Hoseyn Kheyrkhah were mostly centers of attention for audiences who would gradually be drawn to, and become supporters of, the leftist ideology even if at the beginning they had no notion about it.

On the other side were Seyyed Alikhan Nasr, Dr. Mehdi Namdar, and Ahmad Dehqan. Seyyed Alikhan Nasr had studied acting and staging theater shows in France. At the beginning of the constitutional era in 1290, after the National Theater group headed by Mohaqeq Al-Doleh where Nasr was also an active member, was dissolved, he [Nasr] formed six comedy groups and continued his involvement in education of performing arts. During Reza Shah’s rule, he was given the responsibility of running the theater division of the “Institute for Intellectual Development”, which was a government entity. In 1939 Nasr established the Acting School of Art, and eventually in 1940 he bought a section of the Grand Hotel and turned it into “Tehran Theater House”.

In the following years, after Nasr was given an assignment in the Iranian Embassy in India and had to give up his activities in the acting school and Tehran theater, Ahmad Dehqan assumed the responsibility of heading Tehran Theater, and Dr. Mehdi Namdar became head of the Acting School of Arts.

To climb the ladder of success, Ahmad Dehqan, from his young days, was involved in journalism and political activities. In 1941 he became the managing editor of Tehran Mosavar magazine, a position, which alone with his all-out opposition to the Tudeh Party, helped him add membership of Iran’s parliament to his resume. As for his artistic activities, he began by working with Noushin’s group, but later joined Seyyed Alikhan Nasr. In his political activities, he left Qavam-Al Saltaneh supporters to join Razm Ara, but when he saw the troubles that Razm Ara was in, he disconnected with him and decided to serve the [Shah’s] court for further progress. Finally, in 1950, he was shot and killed in the office of Tehran Theater House by a person named Hasan Jafari.

Dr. Mehdi Namdar was among the first students during Reza Shah’s reign who was sent to France to study pharmacology. While in France, his love for performing arts prompted him to study theater while attending to his main discipline. He usually took over several major responsibilities at the same time and among his positions were mayorship of Tehran, mayorship of Isfahan, head of Iran Pharmaceutical Company, head of Tehran University’s College of Pharmacology, member of High Cultural Council, head of Acting School of Arts, founder, and professor of performing arts at Tehran University’s School of Fine Arts.

Acting School of Arts

Following September 1941, the Acting School of Arts, headed by Dr. Mehdi Namdar, began training interested individuals who did not have any political leaning, and at the same time tried to stop the political influence of the first group that was Noushin’s. The Acting School of Arts had an entrance exam and accepted students who had finished ninth grade and after three years of education gave them an acting diploma. His diploma was officially recognized by government entities, which was a major step in giving official weight to performing arts and to encourage interested people to take that profession more seriously.

Due to budget shortage, once every three years the Acting School of Arts accepted volunteers. This school was in fact a solid foundation for the artist’s ongoing activities and subsequent research. A glance at the list of artists who began and ended their artistic education in that school tells the type of service that this establishment and its directors rendered for the expansion and exaltation of theater in Iran regardless of the genre or style.

Lalehzar, A Center for Theater Activities in Tehran

In the 1940s, in addition to musical, historical, and fantasy shows that were based on fictional stories such as One Thousand and One Nights, as well as comedy and ethical shows, which are still part of theatrical shows, major efforts were exerted on creating theatrical pieces based on famous European playwrights. Pieces that were produced for the stage had mostly a distinct social and political flavor. South Lalehzar Avenue, which was Iran’s version of Broadway or West End, had become a center for theater activities in Tehran and was the location where the elite and artists frequented. Most cultural centers, fancy cafes, and expensive stores were in the same vicinity, and it was a point of rendezvous where the intellectuals of the time would gather in the afternoon to engage in discussions of arts or politics.

Most theater groups that played in translated theatrical pieces had somehow leftist tendencies. What was common between right and left groups was the style of their acting, which was tremendously inspired by French theater and artists like Antoine Artaud, Andre Antoine, Louis Jouvet, Jean Louis Barrault, Jean Vilar, Harry Baur, and Sara Bernhardt. Additionally, other directors and actors, including English theater practitioner Gordon Craig and director Max Reinhardt, as well as German actors Emil Jannings and Conrad Veidt were outstanding examples, regardless of familiarity with their styles. For leftist groups, the Russian theater practitioner Konstantin Stanislavski was a prophet. Stanislavski was introduced to Iranian art lovers between 1929 and 1933 by Mir Seyf Al-Din Kermanshahi, who had been educated in Moscow and Tbilisi in various aspects of performing arts and specifically as a set decorator. Practical training of his methods and techniques in “Farhang Theater” that was set up by Abdol Hossein Noushin continued more extensively years later. Although Noushin was educated in France, yet since Stanislavski’s “system” was widely popular in Europe and North America and had many followers, he [Noushin] too chose that style and followed it.

Abdol Hossein Noushin and the Tudeh Party

Abdol Hossein Noushin, as attested by his close coworkers, was the first person in Iran who did theater work meticulously, diligently, and accurately with the criteria set in the western world at the time. He always took to consideration the relevant political issues, artistic needs, new methods of writing and his available tools when he chose plays. Noushin always allocated time for round table reading and discussion, so that all his coworkers could understand the meaning and purpose of the play, and contrary to the past that each actor only focused on his/her role, Noushin wanted every actor to know about every role so that his/her role would be played in relation to other roles. Noushin assigned the roles based on physical traits, artistic abilities, physiological qualities, and even personal leanings of his actors towards relevant issues. When analyzing the play, he would consider the play’s specific nature of time and location, as well as the social standing of each personage, and tried to match every move, décor, costume, and makeup, as much as possible, with the reality of the play. Noushin taught his cast that they should stay away from playing their role in an unnatural way or based on ordinary formulas in an attempt to recreate what they already know about relevant events. He reminded them that for best results they must be truly natural, which meant that while they knew the script well and had analyzed every detail of it, they must remain completely unaware of what would come next and not have a pre-determined reaction. To achieve that, Noushin asked actors to not suffice with what the script said, but to rather use their imagination and think about personages in different stages of life and try to show what they could have done in any given situation. That, according to Noushin, would help the actor to become one with his/her role and show the audience a natural occurrence of that the story entailed.

Two major points that Noushin emphasized greatly was absolute discipline, which would give special value and respect to the profession, and complete disregard of the solfege factor, which would deter the actor from creativity in playing his/her role and would bring the value of work down to the level of a simple narration. Nevertheless, looking at numerous pictures of Noushin’s theatrical roles, and his great emphasis on manner of expression and bodily movements of his cast, suggest that his performances, which were romantically inspired, must have been based on gestures. This was also clear in Loreta’s acting in Alexander Ostrovski’s “Innocent Coupables”, which she played and directed in Kasra Theater upon her return after a long stay in Moscow.

Among the students that Noushin trained and cast in plays at Farhang, Ferdowsi and Sa’di theaters (the last one was indirectly done through Loreta), are Sadegh Shabaviz, Mostafa Oskooyi, Mahin Oskooyi, Mohammad Ali Jafari, Nosratollah Karimi, Ali Mahzoon, Ezzatolah Entezami, Mehdi Amini, Taghi Mina, Mahin Deyhim, Parkhideh, Asghar Tafakori, Hasan Khashe’, Sadegh Bahrami, Tooran Mehrzad, Manoochehr Kaymaram, Azizollah Bahadori, Houshang Sarami, Irene Asemi, Mohammad Taghi Kahnemoui, and of course Hoseyn Kheyrkhah, who was then a leading actor. These were theater and cinema personalities who rendered valuable services to the world of theater in Iran.

Basically, Noushin introduced the most important theatrical movement of the time to Iran, the effects of which are still felt in all theatrical fields through his students and the following generations of students. Following the attempt on the life of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi in 1948, the Tude Party was banned, and Noushin, who willingly or unwillingly6 had become a member of the party’s central committee, was arrested and jailed and the incident was followed by the shutdown of Ferdowsi Theater. Still, the Tudeh Party continued its activities covertly and overtly, held meetings, and printed and circulated its publications under various names. At the same time, Noushin’s friends did not sit still; they opened the Sa’di Theater in Shah Abad Avenue, and Noushin continued planning and selecting the plays and the cast, as well as guiding and leading the actors through Loreta, while in prison and in his hiding place after his escape from prison. A play that at the time went on stage by Loreta and Noushin’s guidance was Lady Windermere’s Fan, which became very controversial. This play placed Irene Asemi in front of the audience for the first time and gained her considerable popularity. For the final decision to choose either Tooran Mehrzad or Irene Asemi for the leading role, Loreta took Irene to the prison, and after Noushin tested her speaking style and her movements, he picked her over Tooran Mehrzad. Other theatrical pieces that went on stage in Sa’di Theater included Gaslight, La Robe Rouge (The Red Cape), Tosca, Eugenie Grandet, Tartuffe, and Montserrat.

Noushin, who was sentenced to three years imprisonment due to membership in the Tudeh Party’s central committee, spent a few months in prison but was ordered by party officials to escape with other imprisoned leaders of the party. He spent a year and a half hiding in Ezzatolah Etezami’s home before leaving Iran with him. He had a bitterly tough time in Moscow far from what he lived for, which was the world of theater, because he was not given any opportunity to continue theatrical activities there. Despite the Shah’s permission for Loreta’s return to Iran, his return requests remained denied; however, his friends hoped that in due time they would be able to get the Shah’s permission and bring him back, but it did not happen until his death. Noushin died in Moscow on 2 May 1971 at the age of 65.

Fall of Theater After Failure of the Oil Nationalization Movement

Following the incidents of 19 August 1953 and the fall of Dr. Mosadegh, the new government’s elements destroyed every cultural institution that belonged to the opposition, and Sa’di Theater also burned down. Each one of Noushin’s actors either escaped or went into isolation. Azizollah Bahadori and Nosratollah Karimi who had gone to Czechoslovakia to participate in the international ceremony of socialist youth solidarity, immediately upon returning to Iran and disembarking the ship got on board again and went back, and years later after finishing their studies received the regime’s permission to return home. Sadegh Shabaviz went to East Germany from Moscow and stayed there. Oskooyis, who were in Paris, went directly to Moscow and stayed there until 1958 and gained more theatrical knowledge. Jafari, Entezami and a few others were imprisoned for a while and released later.

As Mohammad Reza Shah gradually gained full control of the country’s affairs, he forced the opposition into silence and as a result, theatrical groups that were favored by intellectuals were dismantled and theatrical shows lost their sociopolitical aspects. Theater became mostly about translated melodramas, ethical stories, entertaining comedies, and historical pieces or fictional musical tales, and little by little Lalehzar theaters lost their cultural importance and credibility. The last word on this infamy came from Dr. Fathollah Vala, an educated young man who had just returned from abroad.

The Attraction Period

After the assassination of Ahmad Dehghan, Abdullah Vala assumed the management of Tehran Theater. Vala also inherited the managing editorship of Tehran Mosavar magazine from him and continued the same path. When Vala’s younger brother, Fathollah, returned from France, he gave the management of Tehran Theater, which had been renamed as Dehghan Theater, to Dr. Fathollah Vala. Dehghan Theater had always been a competitor for Ferdowsi Theater and Noushin’s group. There, directors like Ali Asghar Garmsiri, Henrik Stepanian, Hayk Garagash, Nosratollah Mohtasham, and Gholam Ali Fekri produced shows that were merely entertaining and no longer attractive. To gain more revenue, Dr. Vala brought foreign dancers to entertain people mostly by showing their bodies and dancing, and gradually theatrical pieces died down and the shows became solely an attraction. With this trend, Dr. Vala opened the door to a new period in Iran’s theater history that was later called “Attraction Period”, because other theater houses in Tehran had to resort to similar attractions to stay in business. In this period, what they called theatrical shows was in fact a cover to evade payment of charges that nightclubs had to pay for their shows. Theaters like “Pars Theater” that could not bring dancers from abroad7, used dancers of Lalehzar cafes and restaurants and popular singers, and even they had drastically reduced the number of their shows. The shows of this period were in fact short acts in which main actors entertained people by imitating ethnic accents. These shows were repeated several times a day, thanks to dances and song performances.

Barbod Theater was the last place that fell into this trend. Since 1926, Barbod Theater, under the leadership of Esmaeil Mehrtash and in collaboration with Rafi Halati, had staged dignified musical shows for interested audiences. This was the theater that introduced stars such as Molook Zarrabi, Abdolvahab Shahidi, and Marzieh to Iran’s world of music; this was the theater where Mir Seyfeddin Kermanshahi built the foundation of real theater set decoration by his unique and innovative creations. And now, the theater that had popularized the Iranian style prologue, had to resort to attractions to keep customers happy and continue the path set forth by Dr. Vala. With this development, Mehrtash stepped down from the theater’s management and usual shows were replaced by popular ones.

Two Other Permanent Theaters in Lalehzar

In South Lalehzar Avenue, across from Pars, Dehghan and Barbod Society theaters, there was another theater, called Guiti, which was mostly known as Sadeghpour Theater after the name of its owner Morteza Sadeghpour. Morteza Sadeghpour was a simple and sincere man who owned a shoe shop, but his strong passion for theater forced him to sell his business and found this theater. He wrote plays and took them to stage with the help of his second wife, Lor, and his sons, Iraj and Manouchehr, who later became famous movie actors and cinematographers. These plays which were mostly historical or adaptations of Shahnameh’s stories included, “Nader, Pesar-e Shamshir” (Nader, the Son of the Sword), and “Bijan and Manijeh”. Sadeghpour had no real schooling, so he had to ask others when writing his plays; however, he was frank and a wisecrack. Those who went to his plays always expected an incident, such as debates and contentions between him and his audiences and did not pay much attention to the play. Perhaps that was the main reason they ever went to see his plays. Sadeghpour was small built and had a rather female-like voice; yet he always played such roles as Nader Shah and Rostam, while actors like Nosratollah Mohtasham, Hooshang Sarang or Akbar Meshkin, with thunderous and resonant voices that struck audiences with awe, always played those roles. That was the reason for his audiences to throw mischievous remarks at him, to which Sadeghpour gave knockdown answers.

Another permanent theater around Lalehzar was Tafakori Theater, located on Melli (Barbad) street, which was in fact the same as Ferdowsi Theater founded by Noushin. After Noushin, Asghar Tafakori, a powerful heavily built actor with a strong voice, who had now become an example of acting in theatrical comedy, bought that theater and put his name on it. He brought his entertaining and happy comedians to the stage of this theater and gained the admiration of his audience. He focused his activities on that theater until the time of his death at the age of 56. After Tafakori, another comedian, Abdi, who was also mildly overweight, took the management of that theater in collaboration with Tehranchi. He tried to continue the same path as Tafakori but could never reach his level. Whether on theater stage or as a movie actor, Tafakori had become a popular national actor.

Return of the Artistic Era

In the 1950s, parallel with the gradual fall of Lalehzar theaters, two theatrical movements began to slowly emerge, the combination of which ultimately gave birth to today’s theater. The first one was the reappearance of the same intellectual theatrical movement of the 1940s, where Noushin’s associates tried to bring back to stage culturally and artistically valuable shows, without any political connotations, and unlike what other Lalehzar theaters would show. The first person to step in was Mohammad Ali Jafari. Jafari began his collaboration with Noushin in 1953 at the Farhang Theater, where Noushin often gave him the leading role of young characters. Following the incidents of August 1953, Jafari, like Noushin’s several other coworkers, was arrested and then released. Upon his release in 1954, Jafari, in collaboration with Shahla Riahi, took to stage of Pars Theater an emotional melodrama called Dangerous Corner, which gained the admiration of art circles. Jafari invited a group of Noushin’s former students and coworkers and tried to duplicate almost the same type of work without any additions or without being able to bring the level of work up to that of Noushin’s. Among Jafari’s stage productions in Dehghan Theater were Gaslight, Lady Windermere’s Fan, The Lady with the Camellias (La Dame Aux Camellias), An Inspector Calls, and Montserrat. He also produced some new pieces for Barbod Theater, including Michael V. Gazzo’s A Hatful of Rain, Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and Jean Cocteau’s The Terrible Parents (Les Parents Terribles) in 1959, which was his last work in that period. Jafari them went to the public sector and joined the group of artists called “Office of Theater Programs”. He acted in their plays and produced shows for “25 Shahrivar Hall” or Sangelaj Theater. His first acting role in that period, which was very successful, was Gholamhossein Sa’edi’s “Behtarin Babaie Donya” (Best Dad in the World) directed by Jafar Vali.

Several years after Jafari’s resumption of stage work, and parallel with his new activities, Mahin and Mostafa Oskooyi, Noushin’d former students and coworkers, returned from their long stay in Paris and Moscow. Oskooyis had been learning the Stanislavski system in Moscow under the direction of Stanislavski’s friend and coworker, Yuri Zavadsky. Upon returning to Tehran, instead of looking for old friends and coworkers to form a theatre group, Oskooyis established the “Anahita Art School” in 1958 and began training art students to later use them for the roles they had in mind. Thus, as they kept their independence, they joined groups that were affiliated with the Ministry of Ars and Culture, with whose help they promoted their educational and theatrical programs, and produced “Othello”, which gained the admiration of theater lovers. Mostafa Oskooyi had an egocentric way in his work and he only included himself and his wife in his plays without ever using any of the experienced actors or former friends in his plays except in one or two occasions when he assigned them minor roles. He always tried to use students whom he had trained for the roles he needed. For that reason, he never had any partners in promotional posters, and only his and Mahin’s names appeared on them; even the name of the leading man who played Othello was left out of the promotional posters for that show.

The night that Othello was played in Farhang Hall8 in front of Shams Pahlavi and her husband Mehdad Pahlbod [Minbashian], as well as the then Minister of Arts and Culture, the acting of two actors, Eduard Balasanian who played Othello, and Mehdi Fathi, who played Roderigo, impressed Shams Pahlavi so much that she sent someone back stage to ask the names of these two players.

Oskooyi was not in good terms with Jafari and critiqued him in newspapers. Jafari, in turn, responded and one criticized the other for different reason. Oskooyi criticized Jafari for not knowing what to do with his hands when playing on stage; Jafari responded by saying that first Oskooyi had to go to him [Jafari] to learn how to speak on stage before criticizing him. Unlike Jafari, Oskooyi never produced the plays that Noushin did; his and his wife’s repertoire included modern classic plays that had never been produced such as, Alfred Jarry’s “Tabagheye Sheshom” [Original title not found], Lillian Hellman’s “The Little Foxes”, Henrik Ibsn’s “A Doll’s House”, William Shakespeare’s “Much Ado About Nothing”, Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire”, Carlo Goldoni’s “The Mistress of the Inn” (Mirandolina), Pierre Beaumarchais’ “The Barber of Seville” and “The Marriage of Figaro”, and other pieces such as “Rostam and Sohrab”, “Tahiti” etc.

In addition to acting and directing, Oskooyi was also a theater instructor and knew himself as the only true promoter of Stanislavski’s “system” in Iran, because he regarded his wife Mahin and himself as the only people educated in the “Art Theater” atelier who had learned the “system” thoroughly. In his classes, Oskooyi passionately emphasized the “System” and rejected every other method used in other educational centers.

Surge in Theoretical Recognition of Theater

Parallel with the activities of artists like Jafari and Oskooyi that were absolutely professional and practical, there were those in the private sector, who, despite taking major steps in both aspects, played undeniable roles in elevating Iran’s theatrical art in its theoretical side. The most outstanding person in that regard was Shahin Sarkisian. Sarkisian was born in 1910 in an Armenian family. His mother was Bulgarian, and his father was Iranian. When Shahin was only 7 years old he was sent to France to go to school, where he mastered French and learned Russian and German languages. Although he was not academically educated in performing arts, he passionately studied and read about various theatrical schools and their founders, both in writing and acting. He returned to Iran when he was 28 years old and was hired by Bank Melli, where he met Sadegh Hedayat and Hasan Ghaemian, while still socializing with the Noushin Group. Following the incidents of August 1953, he gathered a group of theater lovers, most of whom were graduates of acting school, and began talking to them about the developments of theater in the western world. Among the people who went to Sarkisian’s small home, gathered around his table, and drank the coffee that his old mother would offer, were artists like Fahimeh Rastkar, Ali Nasirian, Bijan Mofid, Ahmad Baratloo, Jamileh Sheykhi, Esmail Shangaleh, Abbas Javanmard, Jafar Vali, Nasrin Rahbari, Jamshid Layegh, Esmail Davarfar and a few more. In addition to work on the pieces of playwrights such as Chekhov, Eugene O’Neill, Bernard Shaw, August Strindberg, Clifford Odets, Jean Cocteau, and Pirandello, this group also discussed the potentials of national theater and production of real Iranian plays. In that regard, Sarkisian and his group completely disregarded plays written by Akhundzadeh and Mirza Agha Tabrizi, as well as typical Iranian plays such as “Ostad Noruz Pineduz “ by Mirza Ahmad Khan Kamal al-Vozara (1919), “Jafar Khan az Farang Bargashteh” by Hasan Moghadam (1921), “Jijak Alishah” by Zabih Behrouz (1301 AH), and most importantly “The Rubber Ball” by Sadeq Chubak, who was their contemporary and most probably an acquaintance of Sarkisian (as they had many common friends). They even left out Sadegh Hedayat’s writings and solely focused on two stories of “Mohallel” and “Mordehkhorha”9. Finally after several private shows, in 1953 these two plays, along with “Af’ei Tala’ie”, written by Ali Nasirian, which is a free adaptation of Sadegh Hedayat’s “Dash Akol”, went on stage. With these three plays, although Sarkisian withdrew from the group, “The National Art Group”, directed by Ahmad Baratloo and Abbas Javanmard, declared its official existence.

A New Chapter in Playwriting and University Education

Following this victory, Ali Nasirian wrote a play called “Bolbol-e Sargashteh”, with adaptations of folk tales, which was a step forward in its own time. The stage production of this play by Abbas Javanmard in 1959 gained a great deal of popularity and was invited to France by the Theater of Nations Festival. This was the first Iranian play performed at an international festival.

The activities of National Theater Group opened a new chapter in writing and staging Iranian plays. With translation of Lajos Egri’s “The Art of Dramatic Writing” by Dr. Mehdi Forough, and several courses offered in dramatic arts, the need for a serious forward movement in theater art that had been greatly felt led to writing and production of more plays, and it continued on and on until the fruitful decades of 60s and 70s.

As for university courses on performing arts, the first step was taken by Tehran University’s College of Literature. In the mid-1950s, Dr. Frank C. Davidson was invited to teach acting, directing, make-up, scenic design, theater literature, playwriting, and performing art criticism in that college. Course participants would get a certificate signed by Dr. Davidson upon completion of a four-and-a-half-month course and passing the final exam. A practical result of this course was the performance of Tennessee Williams’ “Glass Menagerie” in Iran-America Society. Like translation of this play, Dr. Forough regularly worked with Davidson as a translator. Other plays that opened the window to a new horizon were Davidson’s productions of Thornton Wilder’s “Our Town”, and Arthur Miller’s “All My Sons” in Dehghan Theater.

After Dr. Davidson, the College of Literature invited Dr. George Queenby for the next academic year to teach the same courses in theater. Participants were mostly the same actors who would take theater courses no matter where they were offered: Bijan Mofid, Parviz Bahram, Fahimeh Rastkar, Jafar Vali, Hooshang Latifpour, …

For the following academic year, Dr. Belcher was invited to the college and helped produce three plays by the end of the year, including Eugene O’Neill’s “Emperor Jones”. A few years later, Dr. Queenby returned to Iran to teach again, and the result of his work included such productions as an adaption of a Herman Melville work, “Billie Budd”, and Eugene O’Neill’s “Long Day’s Journey into Night”. A year later, Dr. Hayden Gray assumed the role of teaching performing arts at the college, and at the end of the year the production of Arthur Miller’s “A View from the Bridge” was prepared to go on stage.

Performing arts educational courses in the college of literature were very useful for both participants and for Iran’s theater, and the need for independent academic colleges for performing arts resulted in establishing one in the following year.

By establishing “The School of Dramatic Arts”, which immediately changed its name to “The College of Dramatic Arts”, higher education of performing arts began independently in a separate college. This college continued and completed the courses that were previously taught in the Open School of Dramatic Arts in the Office of Dramatic Arts.

Office and College of Dramatic Arts and Higher Education of Performing Arts

In 1957, the Office of Dramatic Arts, which was previously called Office of Fine Industries, was established within Iran’s Headquarters of Fine Arts[10]. The founder of this office was Dr. Mehdi Forough, who had finished his studies in music and theater in England, France and the United States before returning to Iran.

The goal of the Office of Dramatic Arts was promotion of performing arts, and it was with that primary goal that this office hired graduates of acting school and made theatrical productions. Actors who were initially hired there included, Abbas Javanmard, Ali Nasirian, Rokneddin Khosravi, Jafar Vali, Jamshid Mashayekhi, Jamshid Layegh, Esmail Davarfar, Esmail Shangaleh, and Khalil Movahed Dilmagani. Other actors such as Ezzatolah Entezami, Hamid Samandarian, and Abbas Maghfourian, who had studied theater in Germany, as well as Pari Saberi, who had studied cinema in France, joined the group. A few years later, Davoud Rashidi returned from France and joined them. The Office of Dramatic Arts had a small hall, where artists used for theatrical performance. Jean-Paul Sartre’s “Huis Clos” [Hell], directed by Hamid Samandarian, and Marcel Achard’s “Voulez-vous jouer avec moâ?” [Would You Like to Play with Me?], directed by Davoud Rashidi, were among the plays performed in that hall.

To promote theater, those who were in charge of the Office of Dramatic Arts decided to produce plays that were 30 to 40 minutes long and show it on Iran Television, which a successful businessman by the name of Habib Sabet had brought to Iran. The goal was to make more segments of the population to learn about theater and to find affinity with it. At first, the shows were translated melodramas, which did not gain any popularity; but gradually, as Iranian pieces were written, played, and appeared on television, people grew fonder and more interested to watch them. Playwrights at the time mostly included Ali Nasirian, Bahrm Beyzai, Akbar Radi, Mohsen Yalfani, and Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi. The Television show, “Hallou”, written and directed by Ali Nasirian, gained more popularity than any other television show and brought many people in front of televisions to watch similar shows. At the time, there were six directors who regularly worked on similar shows and each one directed a show every six weeks. These directors were Hamid Samandarian, Ali Nasirian, Abbas Javanmard, Jafar Vali, Rokneddin Khosravi, and Khalil Movahed Dilmaghani. Then, Davoud Rashidi, Abbas Maghfourian, and Esmail Shangaleh, upon his return from Germany, were added to the group.

Among the activities of the dramatic arts office, which were truly valuable in promotion of Iran’s performing arts were, formation of the “Friends of Theater Association”, with members such as Saeed Nafisi, Ebrahim Khajeh-Nouri, Dr. Mehdi Namdar, Dr. Abuighasem Janati Ataie, and Dr. Mehsi Forough; joining UNESCO’s International Theater Institute (ITI), and celebrating the ITI day; holding an annual competition for writing plays; publishing a biweekly theater bulletin; supporting affiliated groups and providing them opportunities to take their shows to television; taking shows to stage in other cities; and more importantly establishing the “Performing Arts Open School”, to teach the art of writing plays, acting, speaking techniques, scenic design, costume design, makeup, and puppet shows. It was Dr. Mehdi Forough’s dedication and determination in pushing and continuing these courses that led to establishment of “College of Dramatic Arts” as the first performing arts college in Iran.

In its first year, the college of dramatic arts chose twenty-five students for five fields of study by holding an entrance exam. Students received their bachelor’s degree in four years, after completion of general courses in the first two years, and specialized courses during the second two years, with every student spending time mostly with his/her group. Specialized courses included acting and directing, dramatic literature and playwriting, stage lighting, scenic design, and costume design, puppet shows, and cinema.

For one year, Dr. Forough was the head of the dramatic college and the office of dramatic arts. In 1965, the office of dramatic arts became an independent entity by the name of the Office of Theatrical Programs, took charge of Sangelaj Theater, and began new activities. The responsibility of this new office was then given to Azemat Janti, who, in collaboration with Ali Nasirian, Davoud Rashidi, and Ezzatolah Entezami, began planning for theatrical shows.

Sangelaj Theater

In 1965, the construction work on Bistopanj-e Shahrivar (Sangelaj) theater was finished and the theater was given to the office of theatrical programs. The beginning of this theater’s activities coincided with the time when young Iranian playwrights had written numerous plays and were looking for a venue to stage them. These were the plays that were mostly written in modern styles and techniques and had something to say. Therefore, in the new season of 1965, which began in September, the first festival of Iranian plays was held in the theater and met a great deal of enthusiasm. The main objective of Sangelaj, which was a public theater, was to stage Iran’s contemporary plays, because there were theaters for other types of theatrical shows. This policy went on for several years and numerous shows went on the stage of that theater, most of which became very popular and some remained to meet the audiences dislike. The directors of these plays were affiliated with the office of theatrical programs.

A major development during this time was that after almost 15 years, theater in Iran gradually regained its socio-political aspect, which it had lost as a result of suppression by the security apparatus of the country. This was happening through theatrical symbolism or shrouding words in a cloak of riddles. The first step in that direction was taken by Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi. By writing the play “Chub be-dast’ha-ye Varazil”, which was taken to stage by Jafar Vali on the second year of Sangelaj theatrical activities, Sa’edi attracted a big number of young students to the theater. Sa’edi’s collaboration with Vali was very fruitful, and in fact Vali took a major step towards Sa’edi’s fame, like Abbas Javanmard did for Bahram Beyzai. Sa’edi’s works were also directed by others including Davoud Rashidi, Mohammad Ali Jafari, and Ezzatolah Entezami. Basically, in the 60s, a great many plays on the sociopolitical theme were written, which either went unnoticed by security organizations, or completely ignored by the regime because of its strong control over the situation. Of course, later it did not stop the regime to put a number of playwrights, including Sa’edi, in Jail and torture them.

Managers of the office of theatrical programs also took two plays to the Sangelaj stage by older Iranian playwrights, either due to lack of any new plays by newer playwrights, or because of their love for older works. The two plays were, Mirza Agha Tabrizi’s “Tarigheye Hokoomat-e Zaman Khan-e Boroujerdi”, directed by Rokneddin hosravi, and Mirza Fathali Akhundzadeh’s “Sargozasht-e Mard-e Khasis”, directed by Khalil Movahed Dilmaghani.

It seemed like the people at the office of theatrical programs were not greatly interested in bringing other groups to Sangelaj; therefore, when they had no shows of their own, they resorted to foreign playwrights such as Gogol and Plautus and took their plays to stage, pretending they were popular pieces. This was, of course, completely against the theater’s policies, because the purpose of Sangelaj was to only support contemporary Iranian plays and playwrights. But this journey from Iranian plays to foreign plays did not happen overnight. It began with a trip to the past and a play by Mirza Agha Tabrizi; then after “Sargozasht-e Mard-e Khasis” went on stage and liked by audiences, they changed the name of Akhundzadeh to Akhundov for a smoother transition to Gogol to find a way of deflecting from their course. The justification was easier: they were both from the same town and contemporary, and the issues that Gogol had talked about in his work “The Government Inspector “, were also relevant in our country and similar to what Akhundzadeh would say. To move from Gogol to Plautus, his comedy “Miles Gloriosus” or “The Swaggering Soldier” [or “The Vainglorious Soldier”] was played on the stage of this theater that was built to attract masses. But the truth was that Sangelaj was supposed to mainly support Iranian plays, and the theater had to a great extent succeeded in winning its goal.

Between 1967 and 1977, a total of 56 Iranian plays took the stage on Sangelaj, including 8 plays by Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi, 6 plays by Bahram Beyzai, 6 plays by Ali Nasirian, 4 plays by Akbar Raadi, 4 plays by Nosratollah Navidi, 3 plays by Parviz Sayyad, 2 plays by Parviz Kardan, 2 plays by Bijan Mofid, and 2 plays by Manouchehr Radin. Additionally, each of the following playwrights had one play in that theater: Mirza Fathali Khan Akhundzadeh, Mirza Agha Tabrizi, Mohammad Ali Foroughi, Farideh Farjam, Mohsen Yalfani, Abbas Javanmard, Shahbaz Zolriasateyn, Ali Hatami, Iraj Emami, Behzad Farahani, Bahman Farzaneh, Mahmoud Ostad Mohammad, Nader Rad, Ardeshir Keshavarzi, Iraj Saghiri, Sadegh Ashurpour, Kourosh Salahshour, and Bahman Farasi. With better programming, however, that would allow more groups to have performances in Sangelaj theater, more Iranian plays could go on stage, because that was the period when numerous plays with valuable and constructive contents were written. Let it not be forgotten that this was also the time when Shahin Sarkisian was working on Akbar Radi’s play,” Rozaneye Abi” to have it performed during the festival, but he was denied for disqualification of the director, whereas many of the festival’s main organizers were former students of Sarkisian. After that insult, Sarkisian left his involvement and for many years worked only with amateur groups.

Performing Arts Higher Education

The second performing arts college was founded in Tehran University’s College of Fine Arts. This college offered a finalized version of courses taught by Dr. Davidson, Dr. Queenby, Dr. Belcher, and Dr. Hayden Grey in the literature college of Tehran University.

In 1940, the College of Fine Arts was founded under the name of Fine Arts Institute and continued the works of Kamal-ol-molk and Arts and Crafts Industries schools, with collaboration of teachers from Kamal-ol-mulk, Mohsen Foroughi and several foreign instructors, headed by the French architect Andre Godard, to teach architecture, painting and sculpture. In 1952, when Professor Godard returned to France, Mohsen Foroughi became dean of the college and remained in that post until 1962. With resignation of Foroughi, Hooshang Seyhoun took his place, and in 1975, while he was in office, a department by the name of “Music and Performing Arts”, with collaboration of Dr. Mehdi Namdar, was added and Dr. Hakoopian, a music graduate, was put in charge of it.

After the Revolution, the dramatic arts, playwriting, acting and direction departments merged with the performing arts department, and later with its expansion and change of name to the College of Fine Arts, each department became an independent college (College of Architecture, College of Painting, College of Sculpture, College of Music, and College of Performing Arts).

Shiraz Art Festival

In 1975, there were two higher education centers in Tehran for performing arts, one of which was affiliated with the Ministry of Arts and Culture, and the other was in the heart of Tehran University. This was the period when performing arts in Iran were at the peak of flourishing, both qualitatively and quantitatively, and the time was right for more extensive activities backed by another cultural organization. Although much younger than the two aforementioned organizations, this one had more assertions, and the abundance of oil revenues in the country allowed for a healthy budget for it. This organization was National Radio and Television, headed by Reza Ghotbi. Ghotbi was an innovative and educated young man, who, apart from broadcasting news and propaganda for the Pahlavi regime that was his main responsibility, had high aspirations for extensive cultural and artistic programs by gathering together a group of intellectuals and educated artists of the country. Among his planned programs were entities for “Preservation and Promotion of Music”, “Performance Workshop”, “The City Theater”, and Shiraz Art Festival that was in fact the creator of the three aforementioned entities.

The Shiraz Art Festival began in 1967 and was held every year for 11 years. This festival played a major role in promoting Iran’s performing arts.

There were narratives about the initial thoughts that gave birth to this festival, but the most logical was that of Farokh Ghafari, cultural deputy director of Iran National Radio and Television, and deputy director of Shiraz Art Festival. In his interview with BBC Persian’s Mahmoud Khoshnam, aired on Tuesday, 20th December of 2011, Ghafari said that one year after the establishment of national radio and television, Reza Ghotbi told him and a few other coworkers to think about setting up an art festival in Iran, after which they, in collaboration with some musicians and other artists, started planning for Shiraz Art Festival.

Shiraz Art Festival was born to showcase Iran’s arts in front of global audiences, and to familiarize Iranians with the arts of international artists. This festival intended to create a dialogue between arts of the East and the West, while building a bridge between tradition and modernism. During the unrestrained years of the 60s and 70’s, the programs of this festival contained truly amazing pieces in variety, pieces that represented magical ceremonies of the most hidden layers of the Amazon forest, as well as the religious ceremonies of the most remote areas of Tibet, or the most modern and perhaps flagrant artistic expressions of the West.

As for performing arts, not only the festival showed the world some clear models of Iran’s most traditional theater, but it also brought the newest examples of western and eastern theater, so that discussion workshops could be held and opinions on old and new styles in theater could be exchanged. These workshops were participated by some of the most notable art figures of the time (some met each other for the first time). Some of the accomplishments of this festival included a modern Japanese theatrical piece from the heart of Japan that was performed in an international festival for the first time; and the play, “Rostam and Sohrab”, which was performed by India’s Kathakali.

After long years, a look at some of the unconventional theatrical performances in this festival can reveal the greatness and importance of it even further. Among the theatrical pieces some stand out: Jerzy Grotowski’s “Constant Prince”; Tadeusz Kantor’s “Dead Class”; Shuji Terayama’s “Asl-e Khoun” [Original title not found]; Mira Trailovic’s “Hamlet in Basement”; Andre Gregory’s “Alice in Wonderland”; the first world performance of Ted Hughes’ “Orghast”, directed by Peter Brook; Jerome Savary’s “Zartan”; Duro Lapido’s “Oba Ko So” [EN. The King did not Hang], a truly amazing musical play from Africa; Jean Genet’s “The Maids” with an exceptional performance, directed by Victor Garcia; Robert Wilson’s “Ka Mountain”, a 164-hour show with a cast of 47. The theater group, Bread and Puppet’s performance of “Fire”, which was intensely against the Vietnam War, along with a few other works that were done without prior coordination, created a great deal of security snags for the festival’s organizers. And finally, it was the performance of “Pig, Child, Fire”, a controversial play that in 1986 closed the doors of Shiraz Art Festival forever.

As for Iranian plays, introduction of “Ta’zieh” and “Rouhozi” theater in a cultural atmosphere gave them special weight and credit and changed people’s perspective towards the people involved in these types of shows. Creating the “Theater Workshop” was a major and unprecedented step in theater work in Iran. Artists hired for this workshop-either experienced or novice- had to work and gain experience without any commitment; and if they were recognized to have potential, the National Radio and Television, Shiraz Art Festival, the Theater Workshop, the City Theater, and other theaters helped them tremendously to present their works. The only commitment of this group was that they had to do their work full time every day and practice. This was unprecedented and unique, as there was no other group, before or after that, to have the same opportunities in front of it. History shows that the results were positive, and many outstanding playwrights, actors, and directors came out of the theater workshop with various views and styles, yet they were all pioneers in their own type of work.

Although the Shiraz Art Festival did not directly cater to the public, and even some educated people and artists of the time boycotted it, the fact is that this festival tremendously changed Iran’s performing arts and paved the way for their advancement in all fields. That is why later on Iranians watched plays in theaters and on television, or even movies, that were produced with more zest and understanding. Professionals and performing arts students could easily find their ways to Shiraz Art Festival, use its programs, sit down in discussion with the biggest artists of the time, and even participate in their works. Professionals and university professors were often invited to the festival, and groups of students could use all the amenities by paying only 100 tumans, which also included transportation from Tehran to Shiraz and to all different venues, as well as food and tickets.

Festival and Seminar of City Theaters

Following the Shiraz Art Festival on behalf of the National Radio and Television of Iran, other festivals were organized by the competitor, the Ministry of Arts and Culture, which also included artistic theatrical pieces. These festivals included Ars and Culture Festival (1968), Tous Festival in Mashhad (1975), Culture and People Festival in Esfahan (1977), and Festival and Seminar of City Theaters (1976), which was exclusively dedicated to theater and had a special significance in training young people involved in theater in other cities of Iran.

Festival and Seminar of City Theaters, participated by 16 groups from 16 cities, began its activities in spring of 1976, and continued with 11 groups in 1977, and 12 groups in 1978. Its shows were performed in four halls in Tehran, including 25 Shahrivar, Molavi, Dramatic Arts College, and Decorative Arts College. In addition to providing opportunities to stage plays and holding seminars for players and audiences, the festival also held lectures with renowned theater figures of the country on various aspects of theater, which, according to some participants, were even more interesting than the main event. About this festival, chief of the editorial board of Theater Quarterly publication, Laleh Taghian, wrote, “In 1978, there was no progress in the quality of theater work at the festival, and this issue could only be resolved with the ongoing help of education and training, but fortunately lecture sessions could-up to a certain degree- compensate the shortfalls for artists, and not for audiences”.

Although, according to experts, the plays in that festival were not of high quality, but there are some among them that are noteworthy, including “Ramroudis”, a joint production by Reza Danshvar and Reza Saberi from Mashhad; and “Dalou” [Old Woman], produced by Ahmad Bigdeli from Ahvaz.

The purpose of this festival, as stated in its manual, was, “The need to organize an annual festival for theater and cinema is felt to elevate the level of theater throughout the country; to discover theatrical aspects in the national culture; and to create a sense of affinity and enthusiasm for theater among Iranians, especially the youth. For that reason, to help the theater in cities, which has been somewhat successful in recent years (an example was Ghalandar Khooneh Theater in Bushehr), the theme of the festival this year is dedicated to theater in cities, so that by presenting a few plays and by holding discussion and critic sessions effective steps may be taken to promote this art”.

Th Festival and Seminar of City Theaters was the only official theater festival and seminar that was also held in 1978. With the end of this festival, the life of art festivals of the Pahlavi era came to an end and another era began.

Post-Revolution Theater

In the final months of 1978, every aspect of life in Iran was chaotic and stability was lost. The situation was tumultuous, and people were angry; every entity was upside down and prison doors were opened to release political prisoners. Released prisoners found new hopes and were happy for a while that there was no force of suppression to quiet down their voices and they could pour out their hearts. This was true for performing arts, as well. Imprisoned artists were released, groups gathered together again, and raised the sound of freedom. The first wish of all artists was freedom from censorship. Theater groups formed syndicates to defend union rights and to break down the cumbersome limitations of the past. Artists employed by the public sector also disrupted their former structures; they chose their superiors and wrote new manuals. Artists that were released from prison and other groups produced numerous revolutionary shows of various kinds including Islamic, communist, freedom seeking, anti-colonial, and anti-capitalist. Every theater venue came to be of use. Famous and committed actors produced shows for Lalehzar type theaters, and people, even those who had no affinity with theater before, rushed to theaters such as the City Theater and Roudaki Hall, where previously they could not even pass by, because of social and cultural disparity, while ticket prices to these halls were cheaper than Lalehzar type theaters. Plays such as Saeed Soltanpour’s “Abbas Agha Kargar-e Iran National” attracted audiences in university gymnasiums and other public venues, and each performance ended with the audience’s group chants. To see Bertolt Brecht’s “Round Heads and Pointed Heads”, directed by Nasser Rahmani-Nejad, one had to stand in line for a long time, hoping there would still be tickets available. The Number of Brecht’s plays that went on stage in Iran in a very short period of time was inconceivable; plays that included, “Mother Courage and Her Children”, “Fear and Misery of the Third Reich”, “The Mother”, “The Caucasian Chalk Circle”, “Mr. Puntila and his Man Matti”, “The Exception and The Rule”, “The Measures Taken”, “How Much is Your Iron?”, etc.

The Theater’s honeymoon, however, did not last long and as soon as the regime stabilized its footings, merciless strikes began to blow intellectuals and artists. Moreover, the war gave the regime more reason to treat with violence whoever was not indisputably aligned with it. In the arts world, every institution was dissolved and supervisors who were selected by artists were dismissed; the Center for Performing Arts that had replaced Theater Programs Office confiscated every theater venue, and every theater-related activity went under the control of the government. Artists, of course, did not sit idle. They, too, set up their own entity in the same location as the Center for Performing Arts to defend their union’s interests and to maintain their dignity. However, they were unable to last and their center was dismantled.

Saeed Soltanpour, who, before the revolution, as popular among students for playing in “The Visions of Simone Machard”, along with other committed actors, Mohsen Yalfani, Mahmoud Dolatabadi, and Nasser Rahmani-Nejad, had previously established the Theater Society of Iran, and had produced theatrical pieces that showed opposition to the government of the time. After the revolution, his documentary type plays angered the new regime, and he was imprisoned and executed. Other committed artists who had spent time in prison during the Shah’s regime, fled the country and took refuge in different parts of the world. As for the rest, those who were able to leave the country eventually did, and the others stayed put and kept quiet. During the cultural revolution, when universities were closed so that the regime could create some sort of a cohesiveness in every affair, including in culture and higher education, suddenly all was quiet; artists lost their revolutionary appetite; hopes were dashed, and production of unorthodox plays stopped.

Despite the regime’s efforts in organizing various festivals, including Fajr, the work of theater experienced a serious setback. Plays on the themes of Iran/Iraq war or confrontation with the Western culture, which were produced with very low quality, made people to resent theater. Reopening of universities, especially those related to arts, however, prompted students to get involved in production of good theater pieces under the guidance of their instructors. By now, the regime had gradually realized what was beneficial to its existence and had become aware that unnecessary violence towards intellectuals and popular artists had ruined its legitimacy. On the other hand, the regime’s cultural authorities had fully realized that the messy world of theater and the activities of regime-affiliated pseudo-artists, who were taking advantage of the absence of truly talented artists by producing worthless theatrical pieces, would ruin the regime’s face more than bringing real artists back. Therefore, they tried to come to terms with artists who did not focus on any specific political views in their works. In 1987, Ali Montazeri was appointed as head of the Center for Performing Arts and took some constructive steps towards improving the chaotic world of theater that had gradually been descending since the years 1979 and 1980. Montazeri tried to provide opportunities for veteran artists who were not directly against the regime to come back to theater. He organized the “Theater Society” and reactivated theater centers in other cities of Iran. As for international theatrical activities, Montazeri renewed Iran’s membership in ITI, and changed the Fajr Theater Festival to Fajr International Theater Festival. He sent some theater groups abroad and invited international celebrities to Iran as guests of festivals and other art circles. Montazeri also established the “House of Theater”, which became a venue to gather artists together, despite its many headaches and controversies.

There were also developments in performing arts educational centers in Iran. Artists who had the experience and the education in performing arts held various educational courses where many volunteers participated; institutions of higher education included elective theatrical courses in their curriculum, and in addition to theatrical cultural centers five other major colleges began offering courses on performing arts. These colleges were, Tarbiat-e Modares, Performing Arts College in Fine Arts University, Cinema and Theater College in Arts University, Open Art College, and Cinema and Theater College in Sureh University. As of now, there are 16 performing arts educational departments in higher education institutes throughout the country, and about 120 thousand students of performing arts have graduated from these institutes.

For graduates of these courses, there are very few work opportunities, and a high percentage of these graduates or even those with experience never find any opportunity to put their artistic experience to use. Currently, there are only 12 theater halls in Tehran, which is obviously very low for a city of 14 million, and a massive group of those who have chosen that profession.

According to Nasser Habibian, theater groups in post-revolutionary Iran are divided into four categories:

- Students-University, which includes theater groups whose performers and decisionmakers are students and university organizations, and whose producers are solely students of theater or other fields. The most important activities by this group that was performed in universities included holding 15 student theater festivals before 2003, followed by holding the university theater international festival in Iran.

- Commercial-Professional, has income-generation and customer satisfaction as its marked characteristics. This theater, which is supported by the government on an independent budget, is for entertainment only and does not claim any depth of artistic features in its content and form. The themes of this type of theater are taken from current events and are mostly comedy. “Damavand” and “Golriz” are among the examples of this type of theater.

- Professional-Artistic, with experienced and professional producers, who place the highest importance on the content and form of the theater. On the other hand, revenue generation is another definition of its professionalism, and customer satisfaction is not the only criterion. Here, too, government is the decision maker and supporter. Most shows in the City Theater are of this category.

- Occasional-Festival, which is defined within the framework of the government’s programs on various occasions, such as historic, religious, and often socio political events. Programs of this theater are geared towards emphasis of such occasions and have so far been popular among student and professional groups. Fajr Theater Festival is among the examples of this type of theater group[16].

Fajr Theater Festival that began in 1982 and became Fajr International Theater Festival in 1995, has held 32 annual ceremonies and is considered the most important theater festival after the revolution in Iran. The organizing sponsors of this festival that is held on February of each year include, Islamic Guidance Ministry’s Center for Performing Arts, Performing Arts Society of Iran, and International Theater Institute.

A general assessment of the current situation of performing arts in Iran shows that although the state of theater is not as bleak as the first decade of the revolution, yet, despite a considerable number of groups involved in this art, there is still a long way before it reaches a deserving status. Post-revolution artists have not yet been able to create the developments such as those created by artists of the 60s and 70s, in various forms and styles, and take their arts a step forward. Even the veteran artists of the 60s and 70s, who keep on their creative activities, have not yet been able to produce any work more brilliant than their previous works. Obviously, of course, the conditions of the time for artists are different from the previous decades. For example, in the 60s censorship was mostly focused on the political views expressed in theater, whereas the current artists have, in addition, the load of religious censorship, which makes the work more difficult for them.

References:

- Adamiat, Fereydoun, Andisheh Targhi, first edition, Tehran: Kharazmi Publications, Sepehr Printing House, 1977.

- Arianpour, Yahya, From Saba to Nima, Volume 2, Third Edition, Tehran: Pocket Books Company, September 16, 1956.

- Beizai, Bahram, Play in Iran, Tehran: Kavian Press, 1965.

- Jannati Atai, Abolghasem, The Foundation for Drama in Iran, Second Edition, Tehran: Safi Alisha Publications, Nobahar Printing House, 1977.

- Habibian, Nasser, Tehran Theaters from 1868 to 2010, First Edition, Tehran: Afraz Publishing, 2010.

- Drewville, Caspar, Drewville Travelogue, translated by Javad Mohebbi, second edition, Tehran: Gutenberg Publications, Iran Books Publishing, July 1969.

- Dolatabadi, Gholamhosein, and Rahmati, Mina, Shahin Sarkisian, Founder of the New Iranian Theater, First Edition, Tehran: Hadaf Salehin Publications, Peyk Farhang Publishing House, 2005.

- Ravandi, Morteza, Social History of Iran, Volume One, Third Edition, Tehran: Amirkabir Publications, Sepehr Press, 1966.

- Ravandi, Morteza, Social History of Iran, Volume 2, Second Edition, Tehran: Amirkabir Publications, Sepehr Press, 1966.

- Zarrinkoob, Abdolhossein, History of Iran after Islam, First Edition, Tehran: Amirkabir Publications, Sepehr Press, 1976.

- Kazemzadeh, Firooz, Russia and Britain in Iran, translated by Manouchehr Amiri, first edition, Tehran: Franklin Publications, 1975.

- Kasravi, Ahmad, History of Iranian Constitutionalism, Tenth Edition, Tehran: Amirkabir Publications, 25 Shahrivar Publishing House, 1974.

- Mackey, Ebrahim, Theater Policies in Iran Today, M.Sc. Thesis, Farabi University (University of Arts), 1979-78 academic year.

- Malekpour, Jamshid, Dramatic Literature in Iran, Volume One, First Edition, Tehran: Toos Publications, Offset Company, 1984.

- Malekpour, Jamshid, Dramatic Literature in Iran, Volume Two, First Edition, Tehran: Tus Publications, Offset Printing Company, 1984.

- Malekpour, Jamshid, Dramatic Literature in Iran, Volume 3, First Edition, Tehran: Tus Publications, Heidari Press, 2007.

- Momeni, M, B, Four Theaters of Mirza Agha Tabrizi, First Edition, Tabriz: Nil Publications, Ebn Sina Publishing, Nur Press, Winter 1956.

- Nourbakhsh, Hossein, Famous court clowns, Tehran: Sanai Library Publications, 1976.

- Homayuni, Sadegh, Taziyeh and Taziyeh Narrating, Tehran: Jashn Honar Publications, 25 Shahrivar Publishing House, without date.

- Theater Quarterly, Issue No. 1, undated.

- _______________, No.2 Winter 1977.

- _______________, No.3 Spring 1978.

- _______________, No.4 Summer 1978.

- Book of the 9th National Experimental Theater Festival, Tehran: Student Experimental Theater Center, 2006

-

Iran 1400https://iran1400.org/author/iran-1400/

-

Iran 1400https://iran1400.org/author/iran-1400/

-

Iran 1400https://iran1400.org/author/iran-1400/

-

Iran 1400https://iran1400.org/author/iran-1400/