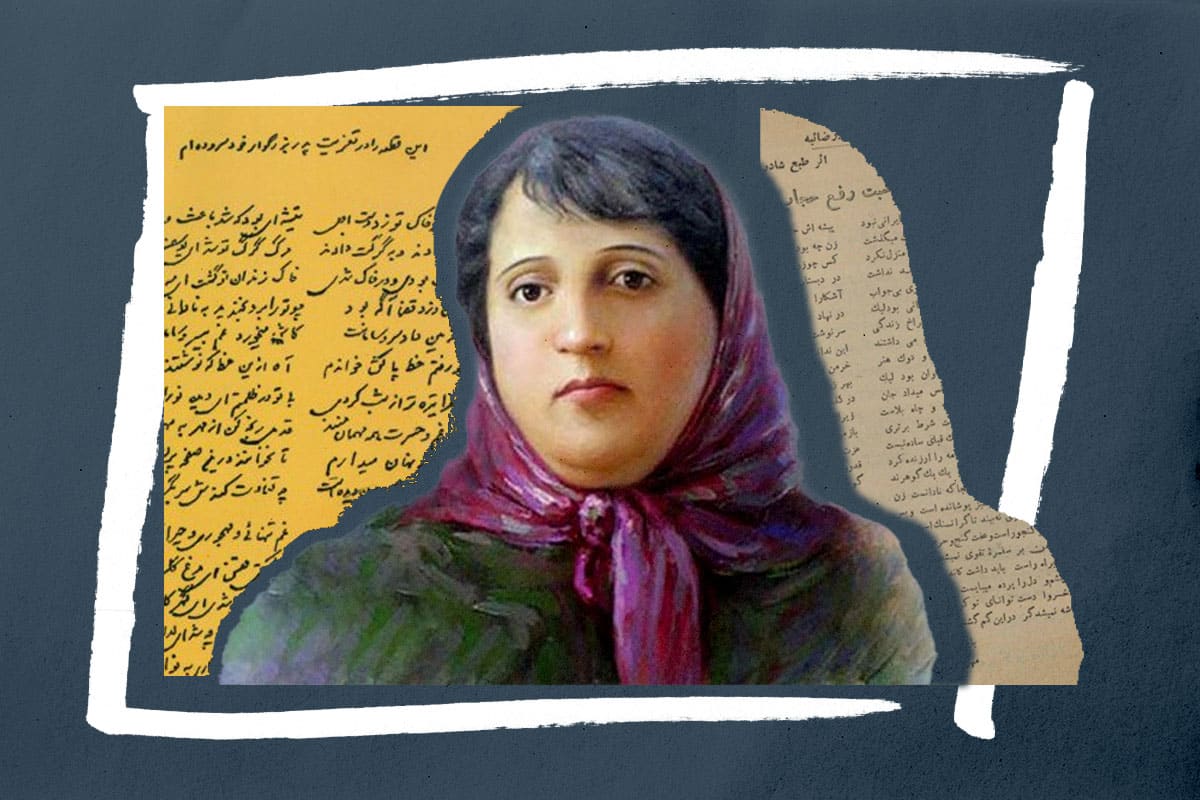

On March 30, 2023, The Iran 1400 Project’s program manager Sydney Martin interviewed Dr. Behnam M. Fomeshi, a Literary Researcher at Monash University, about poet Parvin E’tesami. Dr. Fomeshi examined E’tesami’s life, influences, notable poets preceding her, and her lasting impact on Persian poetry. Read the conversation below:

SM: Could you give some background on Parvin E’tesami’s life and the environment that she grew up in? What did Iran look like at that time?

BF: First, I would mention Parvin’s family, particularly her father Yusef E’tesam al-Molk Ashtiyani, also known as Yusef E’tesami. Her father’s work and translations familiarized Parvin with women’s rights issues. He established the journal Bahar, translating major works from French, Turkish, and Arabic into Farsi. A significant portion of his work in Bahar concerned women’s rights. For instance, the inaugural issue of the journal included a piece entitled Aqideh-ye Zhul Simun: Eslah-e Haqiqi (Jules Simon’s Idea and the True Reform), which ended with the following sentence, “hope of reaching to the caravan of contemporary civilization is contingent on improving the condition of women and educating them.” Furthermore, the second issue included a piece entitled Ekhtera’at-e Nesvan (Inventions by Women).

Yusef E’tesami’s activities concerning women’s rights precede his pieces published in Bahar. Egyptian writer Qasim Amin published Tahrir-l-marʾa (The Liberation of Women), a book on the freedom and rights of women, in 1899 and the following year, Yusef E’tesami’s Persian translation Tarbiyat-e Nesvan (The Education of Women) was published. This indicates Yusef’s familiarity with the contemporary developments of the world and the region, as well as his sensitivity to women’s rights. This translation was published several years prior to the Persian Constitutional Revolution (1905-1911). Yusef E’tesami was among the first to publish on this issue in Persian, and this book was the earliest book dedicated solely to women’s issues written or translated in Persia. Parvin’s exposure to this content informed her writing. Her ideas, as expressed in her work, show close affinity to those of Tarbiyat-e Nesvan. Yet, while her father contributed to advancing women’s rights through translation, Parvin did so through writing poetry.

Now, we can zoom out and have a look at the nation. Parvin lived in the first half of the twentieth century, an eventful period both on the global scale and the national one. During her short life, she witnessed some of the most important events in the history of modern Iran, including the Constitutional Revolution, the prorogation and bombardment of the Majles (Persian Parliament), and the First World War. After the Constitutional Revolution, the country faced a period of chaos and insecurity or, to borrow from Ervand Abrahamian, a “period of disintegration.” In this post-revolutionary period, Persia dealt with major problems such as revolts, assassinations, division into spheres of influence by Britain and Russia, hunger, and insecurity. Parvin also witnessed the 1921 coup d’état and Reza Shah’s modernization and autocratic rule, which led to her increased sensitivity towards the sociopolitical situation of her homeland.

SM: That is a fascinating period to live during and especially interesting to see how Parvin’s father was himself a significant figure. What other ideas did Parvin E’tesami encounter in her life that impacted her poetry?

BF: As far as events are concerned, I’ve already mentioned the Constitutional Revolution, the bombardment of the Majlis, the First World War, the unstable condition of the country, and the relative stability that Reza Shah brought to the nation. As for ideas, I would like to mention the significant development in attitudes toward women and their position in Iranian society. Parvin was exposed to these developments not only through reading, particularly of her father’s translations, but also through attending his meetings with his friends. Even when she was a child, she sat by his side for hours and listened to his conversations with friends. Considering Yusef E’tesami’s writings and translations, as well as the social condition of the country, there is no doubt that women’s rights were discussed in these meetings. Thus, Parvin became familiarized not only with the issue of women’s rights, but also with its intersection with other social, political, and cultural issues of the country. For instance, in the poem Du Mahzar (Two Courts), a dialogue between a wife and her judge husband, Parvin mentions the corruption of the judicial system, emphasizes the value of often-ignored housework, and depicts the role of a housewife as more significant than that of a judge. This poem indicates Parvin’s awareness of the interrelations of women’s rights with other social and political issues of the nation.

Another factor contributing to Parvin’s awareness of women’s rights was the American School for Girls in Tehran, established by American missionaries in 1874. In 1922, Parvin entered the school as a student and eventually taught there after graduation. The school familiarized her with Western literature and modern ideas and also published the journal Alam-e Nesvan (The World of Women) for more than a decade. Among the first in Iran to be devoted to the issue of women, the journal published pieces on the progress of women in other countries, both Western and Islamic, and encouraged readers to change the condition of Persian women for the better. The longest-lasting journal in that field at its time, Alam-e Nesvan published pieces on the participation of women in political activities and criticized early marriage and veiling. Contributors to the journal were American School for Girls graduates and the content of the journal likely indicated the topics discussed and studied at the school.

With over forty sales representatives throughout the country, Alam-e Nesvan played a significant role in educating Persian readers, the students of the school, and Parvin in particular. It was in this context that she gave a talk entitled Women and History and recited her poem Nahal-e Arezu (Wish Sapling) at her graduation ceremony. The talk highlighted the different conditions of women in the East and the West, while the poem emphasized the significance of education for women. Both were also published in Alam-e Nesvan. Interestingly, Nahal-e Arezu was so controversial in defending women’s rights and challenging the patriarchy that Parvin’s father did not include it in the first edition of Parvin’s Divan (collection of poetry) so as not to incite akhunds and the laity alike.

SM: For our listeners who may not know, could you explain what akhunds are?

BF: Akhunds are Muslim religious scholars. So, in this context, this means that patriarchy was so pervasive that support for it was not just coming from akhunds, but also among the laity. Muslim or not, they still believed so strongly in this idea of patriarchy that a poem challenging this idea would incite problems or dissatisfaction. That is why Parvin’s father decided not to include this poem in the 1st edition of Parvin’s Divan.

SM: Fascinating, thank you.

At the Iran 1400 project, we’re always thinking about the bigger picture throughout the century. With this in mind, what significant poets were around before E’tesami’s time and how was the environment for women poets in general? You specifically mentioned in your paper Zhaleh Alamtaj Ghaemmaghami, Zandokht Shirazi, and Tahira.

BF: Yes, so these three poets that you mentioned were more or less contemporary. They faced many hardships, but the most important thing I would like to mention is that these female poets were not taken seriously. And when I say this, I mean they were not taken seriously by anyone. So, it is not just the question of the gender of the poet, but the overall patriarchal values of the society that made these poets unheard. Still, although their audience was very limited, these female poets tried to express themselves in poetry and criticize the patriarchy.

SM: Do you think that E’tesami used these women as inspiration for her poems? Do you see any links there?

BF: Actually, I haven’t worked on the very specific links between Parvin E’tesami and the poets that came before her, but what I would mention is that Parvin was very well aware of the tradition of Persian poetry. So, although I have no evidence that Parvin read, for example, Tahereh’s poetry, I can tell from the poetry that Parvin wrote that she was definitely familiar with that tradition and most likely knew about Tahereh, for example, or the other women poets in the history of Persian poetry.

SM: And you can tell that just from the style and stanzas and format of her poetry?

BF: Yeah, exactly. Just from the style of the language that she used, you can say she was already aware of that.

SM: Interesting. Thank you. So how does Parvin E’tesami’s poetry challenge traditional gender roles and patriarchal norms?

BF: So, from among various poems Parvin wrote, I would like to focus on a single poem titled Bazestadeheem (We Are Still Standing.) In this poem, Parvin introduces the modern concept of “right” as in “human rights” in contrast to hagh in the tradition of Persian poetry, which signified “true” and “The Ultimate Truth,” that is, God. So you can see a kind of secular modern movement in Iranian society reflected in the language used in her poetry. So a word already in existence in the Persian language transformed from something religious into something secular, which you can see in the word hagh, meaning “right.” This poem also refers to the equality of men and women. E’tesami acknowledges the terrible lack of equality in Iranian society, yet, she doesn’t ignore the role that women themselves play in their misery and she somehow casts them responsible for this. This leads the women to take a more active role in the situation, and not just consider themselves victims. Parvin felt that if their condition was not good, maybe women were also responsible and needed to do something themselves, which I think is a very important point we should take into consideration when we are talking about Parvin E’tesami’s feminism.

I would like to read a few lines from this poem so we can talk more about these ideas.

|

بازایستادهایم We Are Still Standing زان دم كه پا به شارع هستی نهادهایم گامی دو راه رفته و گامی سِتادهایم From the moment we (i.e. women) entered the thoroughfare of existence, We have been stopping after every two steps. بنیان آفرینش ما مرد و زن یكی است در شاهراه علم چرا ما پیادهایم؟ We -men and women- share the essence of creation, Why are we afoot on the highway of knowledge? !از حقِ مردمی، ز چه رو دست ما تهی است؟ فرزند آدمیم، نه ابلیس زاده ایم Why are our hands empty of the rights of humanity? We are children of Adam, not born of Satan. ما را خدا مگر نه سر و عقل و هوش داد در پشت سر فتاده چرا چون وِسادهایم؟ Did not God grant us head, reason, and intelligence? Why do we fall behind like a pillow? در زیر پای خویش شدستیم پایمال با دست خود حقوق خود از دست دادهایم We have been downtrodden under our own feet. We have lost our rights with our own hands. گر بیهشان ز باده خرابند، ما ز جهل ما بیهشانِ بی خبر از جام و بادهایم While drunks are senseless from wine, we are from ignorance. We are senseless without any cup and wine. سیلی چرا خوریم؟ نه ناچیز پیشهایم منّت چرا كشیم؟ نه مسكین جرادهایم Why slapped in the face? We are not worthless. Why cringe? We are no poor locusts. تا گوش داده، طعنهی پیكان شنیدهایم تا بال و پر گشوده به دام اوفتادهایم As we listen, we hear the barb of an arrowhead. As we open our wings, we are trapped. گنگیم زان سبب كه همی بر دهان ما مشتی رسیده تا به سخن لب گشادهایم We are speechless since we were beaten in the mouth As we opened our mouths to talk. چون شمع، وقت گریه عبث خنده كردهایم از سوختن گداخته باز ایستادهایم Like a candle, we have laughed when we should have cried. We have stopped melting while burning. هر طایرِ ضعیف شود شاهبازمان از بس كه چون كبوتر و گنجشك سادهای We fall prey to any feeble fowl as we are naive like a pigeon or a sparrow |

In this poem, you see this idea of equality of men and women. Parvin challenges the patriarchal system, yet she counts women responsible for the situation so that they can take an active role in doing something to change their condition for the better. You can see this in the stanza below:

|

در زیر پای خویش شدستیم پایمال با دست خود حقوق خود از دست دادهایم We have been downtrodden under our own feet. We have lost our rights with our own hands. |

Here the words خویش kheesh (self) and خود khod (own) refer to the idea of women also bearing responsibility for their terrible condition. Furthermore, you see this idea of human rights here too. E’tesami is one of the first poets to refer to human rights in such a way in Persian poetry. This is important not only for feminism but for modern Persian poetry, as Parvin contributes to bringing modern concepts into Persian poetry.

SM: How was a poem like that perceived by women at the time?

BF: I can say this poem was well received by the women’s audience at that time because it was published in the journal Alam-e Nesvan (The World of Women.) The readership of the journal was, you could say, the more “enlightened” portion of Iranian society, so the readers of that journal cared about this issue. They wanted to do something to change women’s condition for the better, and I think they were open enough to accept their part in the terrible condition of women. So, of course, this idea of criticizing patriarchy was accepted among those people. I think this also helped them move a step forward and see their active role. That’s also an important point, not just about the poem and the poet, but also about the readership and the audience and the reception.

SM: That’s interesting that they’re able to take self-criticism, that does say something about the readership.

So you in part already answered this question with the last poem that you read for us, but what other themes and symbols does Parvin use to convey feminist ideas?

BF: That is a very good question. There are many different themes and symbols I can mention, but here I would particularly mention Parvin’s treatment of the term “spindle,” which illuminates her endeavor to celebrate women. The spindle is considered a feminine tool in Persian literature and one can find such examples in the poetry of Ferdowsi and Vahshi. It has been used in Persian poetry disparagingly to belittle men by being designated as a tool used by “the feeble sex.” While “true men” deserve to use “manly” tools such as arrows and daggers, cowardly men deserve to use a spindle. One can find more examples of this in the works of Rumi, Sanai, and Nezami. So, as you can see, the giants of Persian poetry somehow enforced such ideas in the history of Persian poetry. In contrast, in her poems that are either directly or indirectly about women, Parvin turns the spindle into a symbol of feminine pride. In Julay-e Khuda (God’s Weaver), for instance, she introduces dook-e hamat (the spindle of endeavor.) In another poem, Ganj-e Aft (Treasure of Chastity,) she writes of dook-e honar (the spindle of art.) The fact that Parvin writes about dook-e khard (the spindle of reason) in the poem Fereshte-ye Ans (Angel of Affection) not only indicates her elevation of women and the feminine “spindle,” but also shows her conscious effort to challenge the supposed mutual exclusivity of affection and reason to depict a more comprehensive picture of women.

There is a very pervasive idea of the mutual exclusivity of affection and reason. So there is a binary position of affection and reason, with affection belonging to women and reason belonging to men. This binary posits that men should be reasonable and not affectionate, and women should be or are affectionate and not very reasonable. This mutual exclusivity, this binary position, is so pervasive, and not just in Persian culture. It is universal and you can find it more or less everywhere throughout history. But this poem, Angel of Affection does not exclude reason. It brings the spindle of reason. So, what Parvin does is to challenge this supposed mutual exclusivity of affection and reason in order to depict a more comprehensive picture of women as human beings who are both affectionate and reasonable.

SM: How does E’tesami’s poetry differ from other women poets of the 20th century in both themes of the topic as well as in style?

BF: That is a very good question because Parvin is unique on different levels. She employs traditional forms and traditional language that are heavily indebted to and reminiscent of the heritage of Persian poetry. And there are so many references to domestic affairs and items. Parvin wrote in the early 20th century, which is the time that modern Persian poetry was born, or evolved, out of the effort of a few generations of Iranian writers. This culminated in Nima Yushij’s poetry, who is known as the father of modern Persian poetry. At that time, Persian poets were busy experimenting with forms of Persian poetry. Forgetting about the ghazal, qasideh, and various forms of Persian poetry, they tried to do something different. Nima Yushij developed something that is called Shar-e No (New Poetry.) This is significant because Parvin wrote in the traditional form, which made her different from most of the major modern poets. All of these characteristics make Parvin’s poetry different from other poets of the 20th century, both men and women.

SM: And has E’tesami’s poetry influenced the poets who came after her?

BF: As far as form is concerned, not much, because her form was traditional and the dominant idea of form in modern Persian poetry has been modern. However, as far as ideas are concerned, definitely. Parvin had an impact on later poets, women and men in general, because she brought modern ideas into poetry that were later employed by other poets and writers.

SM: And why do you think that Parvin’s themes emphasizing women’s rights have been overlooked compared to the other themes in her poetry?

BF: Very interesting question. Unfortunately, the traditional forms and the language and the many references to domestic affairs and items overshadowed Parvin’s innovations, both in language and content, which led to negligence toward her poetry. Readers were already dealing with the controversial poetry of Forugh Farokhzad, who was rebellious both with her content and with the form of her poetry. Her form was also part of Shar-e No. The content was so rebellious that it was unprecedented in the history of Persian poetry. So, when the readers were dealing with this kind of poetry, for example, they were no longer sensitive enough to the significant contribution of Parvin, a modest poet writing in the traditional form. The form and the language that Parvin used reminded the reader of the patriarchal Persian poetry, and just needed a higher level of sensitivity on the part of the reader to go into the poem and engage with it.

SM: Since Parvin E’tesami’s death, how has the environment been for women poets? I know this is a complicated question because I’m sure it got better and then things fluctuated with the transition of the Pahlavi monarchy into the Islamic Republic, but I’m curious if you could provide that sort of timeline and its effects.

BF: I would like to focus on the point that it “got better.” You correctly mentioned the difference between the Pahlavi era and the era of the Islamic Republic, but one thing that just got better and better was women’s easier access to public education. This started during Parvin’s lifetime, due to the efforts of Iranian intellectuals and Reza Shah Pahlavi’s modernization. It only accelerated in the period under Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi and throughout the Islamic Republic. This easier access to public education for women led to the emergence of learned women who could write poetry. Additionally, the modern publishing industry contributed to the ever-increasing number of published women poets who could reach a much wider audience. Moreover, the rise of social media in the last two decades has not only made poetry more accessible and easier to share, but also helped women poets circumvent official censorship, a problem they often face in Iran.

SM: When I think of censorship within the Islamic Republic, I often think about, say, censorship over more sexual themes. Has writing about “taboo” topics become easier for women?

BF: To be honest, they are still today considered taboo, but, due to social media, women poets are expanding the frontiers of subjects and themes in Persian poetry in the public arena. Here, I would like to mention Sarah Bahram, a female poet from Iran who publishes her poetry on Facebook. Her poetry deals with the subjects and themes that you mentioned, and it is quite open and expressive. This is due first of all to the courage of Iranian women poets and it is the result of social media. If there was no social media, the other option would be the official publishing industry. A poet would not get permission to publish such poems through the publishing industry. Another way would be to read to or distribute it among friends, but that would not have much impact. So this access to social media is a very significant contribution to Persian poetry through the expansion of the frontiers of certain themes and subjects considered taboo. They are no longer just for a very limited circle of close friends of the poets, rather, it can reach a wider audience. If it wasn’t for Facebook, I would have never known someone like Sarah Bahram and her poetry.

SM: The topic of social media is a good one to lead us to the last question that I have today because social media played such a large role in the Woman, Life, Freedom protests. How can we use Parvin E’tesami’s poetry when looking at women’s rights in Iran today? And what is the importance of poetry and the arts as it relates to the protests?

BF: Thank you so much for this question. Poetry is interwoven with Persian culture. You can trace the dreams and aspirations of the nation in Persian poetry. Parvin’s poetry in particular reminds us that the young Iranian generation supporting Woman, Life, Freedom is not alone now and it never will be alone. This brave generation is standing on the shoulders of giants, including Parvin. Iranian women can see themselves in the mirror of her poetry and can trace the three themes of women, life, and freedom in her poetry.

Once again I would like to refer to the poem Bazestadeheem (We Are Still Standing)

|

بازایستادهای We Are Still Standing |

Just from the very beginning, the title itself, We Are Still Standing is so contemporary. It refers to the continuous attempt and the fight of Iranian society for equality

|

بنیان آفرینش ما مرد و زن یكی است در شاهراه علم چرا ما پیادهایم؟ We -men and women- share the essence of creation, Why are we afoot on the highway of knowledge? !از حقِ مردمی، ز چه رو دست ما تهی است؟ فرزند آدمیم، نه ابلیس زاده ایم Why are our hands empty of the rights of humanity? We are children of Adam, not born of Satan. |

“Why are our hands empty of the rights of humanity?” is questioning why their hands are empty of human rights. You can see, as far as the content is concerned, this poem is so contemporary it could have been written today. This idea of Parvin being this contemporary helps Iranian society move toward what they want because they realize that they are not alone. Historically, Iranians have all these giants, including Parvin, to help them move toward what they want. If you think about the poetry by Parvin E’tesami, not only We Are Still Standing, but also other poems I haven’t mentioned, you see that Iranian girls and women read these poems that reflect their current situations. They realize: “Wow, this is us! This not having human rights is us! This not being equal with men is us!” So, I think this is so significant in the Iranian context. Of course, poetry is important in any society, anytime, anywhere. However, in Iranian society, it has a very high status, not just among the learned, more elite sections of the society, but among the wider public, too. Everyone knows these poems, they have been exposed to them on different occasions and they see themselves in such poetry.

SM: I think that that is a really great note to end on, to tie it all back to the past, the present, and into the future. Is there anything else, that you wanted to talk about that we didn’t have a chance to cover today?

BF: No, the questions you asked today moved very smoothly from the history and context that inspired Parvin and into the present time. Thank you for inviting me to speak on this topic. I appreciate this chance to talk about Parvin E’tesami, whose modern ideas are often ignored because they are put into the traditional form and language.

SM: Thank you so much for your time today. This was a great conversation.

Behnam M. Fomeshi specializes in comparative literature and is interested in Iranian Studies, American Studies, and, in particular, the intersection of the two. He is a Humboldt Foundation alumnus and a Research Fellow at Monash University (Melbourne, Australia) and is conducting research on the Persian reception of American literature. His works have been widely published and his monograph, The Persian Whitman: Beyond a Literary Reception, was released with Leiden University Press.

-

This author does not have any more posts.