About this Article

“The search for truth shall drive out ignorance.” –Tahirih (Qurratu’l-‘Ayn)

The women of Iran are intimately familiar with repression and segregation, and freedom has many meanings. They are amply tested, living under the forces of patriarchy and oppression. Iran’s mandatory dress code—veiling—is but one of many restrictions that regulate and control women’s bodies and shape their sense of agency and freedom. Although its origins are uncertain, veiling is an ancient Iranian custom. It became institutionalized under Islamic law (Sharia) beginning in the 1500s and was later used as an instrument for women’s segregation and isolation from the public sphere. Until the mid-1900s, Muslim women were confined to segregated quarters—whether in their homes or out—while this was not the case for the country’s small non-Muslim population of Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians, and Bahá’ís. The practice of veiling includes covering women’s bodies down to the ankles and wrists. At one time in the country’s history, the clerical order required women to wear the veil. In 1936, a newly established monarchy ordered women to remove the veil, only to revoke the rule five years later, reinstating mandatory veiling. For another brief period, between 1941 and 1979, wearing the veil was an individual choice dependent upon the approval of fathers, husbands, and other patriarchal figures.

Since the 1979 Iranian Revolution, all women are legally obligated to wear some form of hijab (headscarf) in public, even non-Iranian women. The Islamic Revolution has introduced all sorts of legal and social restrictions impacting the lives of women, who lag far behind in legal status when compared with men. In 2015, the World Economic Forum ranked Iran among the least gender equal countries (141 out of 145). Since the 1990s, acceptable attire for Iranian women includes the hijab, or headscarf, and a long coat, and Islamic religious police are authorized to punish or arrest women who violate this dress code. Typical punishments include up to two months in prison and a fine of about $25 USD. At home, among family and friends, there is no legal obligation for women to wear the headscarf. Yet should a non-family male or a service provider visit the home, women are obliged to cover their hair to ensure an overall “modest” appearance.

Veiling practices are not monolithic but vary across cultures, regions, and eras. And while veiling is undoubtedly supported by a great number of women, it is not supported by all Iranian women. Yet it is important to note, without criticizing women who embrace veiling, that Iranian women do not have the option to not veil. That bears repeating—whether they want to or not, women have no legal ability to not veil themselves. This is rather remarkable. One may be forced to sit in a certain seat or one may choose not to sit on a certain seat, but we also know that there is a difference between choosing to sit and being required to sit. Compulsion removes pleasure. It induces control. Thus, while both results offer matching taxonomic realities—sitting in a particular seat—each carries a very different teleological assumption. Such realities speak of the intentions behind certain activities and how these intentions impact the societies in which they are borne out.

Before the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the legal marriageable age for women was 18. After the revolution, it was 9. In 2013, it was settled at 13. The initial change in the law followed the Islamic practice of allowing a girl to be married off by her father at puberty. However, the change that resulted in raising the age of marriage for women to 13 came about through advocacy for women’s rights on the part of a 13-woman parliamentary caucus in the Sixth parliament during the reform era (1997-2005). These women represented roughly 5% of the total parliamentary—a number that, to date, has not been equaled. The age at first marriage in Iran has steadily increased to the early 20s as a result of an increase in Iranian women’s educational attainment. In 2003 04, women earned almost 50% of bachelor’s degrees, 27% of master’s degrees, and 24% of PhDs (Bahá’ís—an Iranian religious minority—are prohibited from pursuing higher education).

Yet within impoverished households, underage marriage continues.

A woman who wishes to marry must get permission from her father, paternal grandfather, or a civil court. Legally, there is no such thing as rape between spouses. Divorce laws are no longer under the authority of secular family courts where once wives and husbands had a comparable right to divorce. Now, only husbands have a unilateral right to divorce. A woman’s custody rights have also been limited. Laws referred to as obedience/ disobedience and maintenance (Tamkin/Nasheze and nafaqa) stipulate that the husband “maintains” his wife and she, in return, obeys him. That is, under the law, a husband has absolute rights over his wife—encompassing her sexual availability as well as his ability to deny or limit her ability to work outside the home. The temporary marriage law (Sigheh) permits temporary marriage—for sexual relationships—between any man, married or unmarried, and an unmarried woman (virgin, divorced, or widowed). There is no limit on the number of temporary marriages a man can have, and these relationships can last from a few minutes to a lifetime.

Other post-revolution legal changes regarding women’s rights include the removal of female judges and a ban on the appointment of women as judges. Women cannot attend, let alone participate in, public athletic events. They have no legal protections against employer discrimination. Women are not free to travel or obtain passports without a male guardian’s written permission (as a result, employers often prefer to hire men, who can travel freely). And amid sizable progress in education access, Iranian women’s share of labor force participation and employment hovered at only 14% in 2006 and 17% in 2016. Their unemployment rate was 28% in 2011—twice men’s rate, though one in three Iranian women holds a bachelor’s degree.

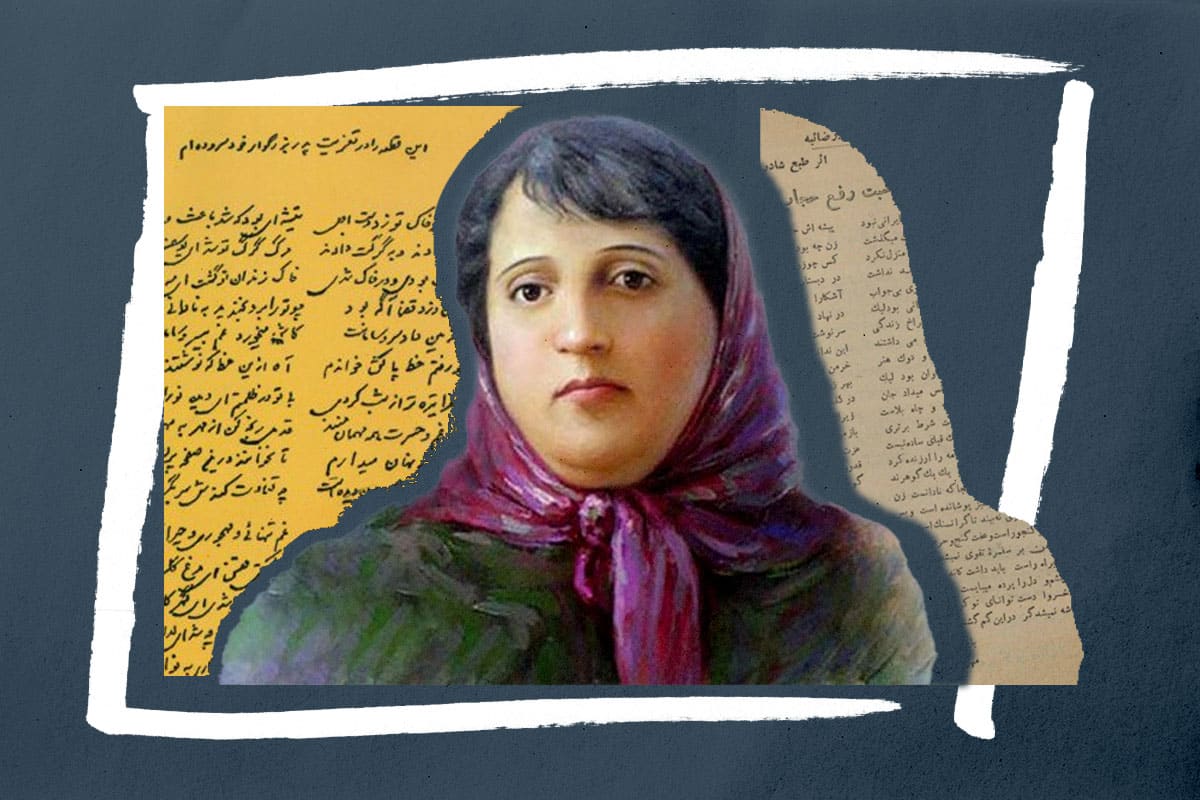

Beyond the quantitative numbers, veiling—and other discriminatory legal restrictions—has a qualitative effect on women’s lives. These laws can render women invisible, insignificant, silent, and absent in public spaces. When a woman decides to break these laws, the results can be serious, even life-threatening. Such was the case with a mid-19th century Iranian poet, Tahirih (1817-1852), quoted at the opening of this article. Tahirih (also referred to as Qurratu’l-‘Ayn) was one of the first Iranian women to defy tradition and publicly remove her veil. She declared that the time for women’s emancipation was nigh. Her poetry, which astonishingly survives, is filled with references to justice and personal freedom. Tahirih was fortunate to have had a father who was a scholar and a forward-thinking man, and her mother was a well-educated religious scholar, a rare achievement for Iranian women at the time. Though hidden behind a curtain, Tahirih received a home education under her father’s tutelage. Privately, she studied Persian and Arabic literature, jurisprudence, and theology.

Eventually Tahirih moved from private to public scholar and challenged the religious rulers of her day, publicly demonstrating women’s capacity to think, reason, and write. Fittingly, she even embraced a new religion—the Bábí religion, forerunner to the Bahá’í Faith. As part of this new practice, she was the lone woman in attendance at a seminal gathering of prominent Bábí men in Badasht, a village in northern Iran. The aim of the gathering was to announce the new religion and demonstrate its break from Islamic law. Tahirih herself demonstrated this break by having her head and face unveiled before the all-male gathering.

Through her bold act, Tahirih was revealed as a threat to her society, to the expectation that women remain private—unseen and unheard in public spaces. By violating the strict norms of society she had defied tradition and entered male spaces of self-expression, thinking, and discourse. Her actions would have severe repercussions. She was arrested by the government, falsely accused of murder, held under house arrest, and executed at the age of 36. To this day, discussion of Tahirih’s story is not permitted in Iran.

Iranian feminism

Feminism in Iran and the diaspora is complicated. What some call “Islamic feminism” refers to feminists who think that legal reform is possible only within the Islamic teachings or the Shari’a. Islamic feminists engage with institutions of power in Iran, including the clergy, in formulating reforms to eliminate discrimination and gender inequality.

The other category of Iranian feminists includes secularists who favor human rights, civil society, civil governance, and democratization. Secular Iranian feminists describe repression and marginalization under the existing cultural and political milieu. They argue for the equal treatment of citizens before the law, including equal rights and obligations. In other words, secular feminists believe that the state and civil society should protect the civil, political, and social rights of men and women equally.

Challenging oppression

For nearly 40 years, the Iranian women’s movement has proven a steady force and voice for women’s equal rights in Iran. Over many decades, nonviolence has been the most powerful feature of the women’s movement. Nobel Peace Laureate and the country’s first female judge, Shirin Ebadi is an Iranian lawyer who was imprisoned for her work defending the rights of persecuted others. She has described how the women’s movement persists, despite repressive laws including legal stoning, sanctioned male-polygamy, and street police raids against women who violate the dress code.

One example of women’s activism took place on June 12, 2006, when both men and women gathered on one of Tehran’s major public squares. Prior to their arrival, they had fanned out through the streets passing out a pamphlet, Why We Don’t Consider the Present Laws Just. As the organizers arrived at the square to begin their demonstration they spotted a small group of police cars headed for one side of the square, while police on motorbikes, wearing riot-gear helmets, took position in another section. Within minutes, the police were everywhere. They ordered everyone to leave the square, but blocked all of the exit paths. After spraying tear gas, the male police officers attacked the men while female officers attacked the women. The police dragged the demonstrators into police vans, forcefully ending the demonstration before it could truly begin.

Soon after, leading women’s rights activists, including the journalists Noushin Ahmadi Khorasani and Parvin Ardalan, met at Shirin Ebadi’s office. It was here that they planned to launch the One Million Signatures Campaign. Their goal was to gather a million petition signatures demanding an end to the government’s discriminatory laws against women. On the day of the official campaign launch, police and security officials blocked the entrance to the building. The launch organizers responded by gathering on the street to distribute petitions. Security forces were unable to stop them.

The campaign’s goal was to secure human and women’s rights in Iran, explains Parvin Ardalan, one of the founders of the campaign. It advocated for equal rights for both women and men in relation to marriage settlements, inheritance law, criminal law, and divorce. The campaign’s biggest achievement was its ability to draw women from all walks of life—secular and religious, young and old, rural and urban, wealthy and impoverished. Women brought the campaign to people in public spaces—on public transportation, in shops and offices, and from home to home. Women also engaged with both men and women to secure signatures and raise consciousness about Iranian women’s lack of rights. The campaign continued for five years. For their roles, Ardalan and Khorasani, along with other participants, received three-year prison sentences.

The campaign brought about parliamentary action that gave women inheritance rights over their husband’s property and entitled female victims of road accidents to receive the same amount of “blood money” as men (before the passage of the new law, women received only half the amount paid to the men). The parliament also prevented the passage of the Family Protection Bill, which would have mandated women to pay a tax on their fiancé’s dowry gift (Mehrieh) and allowed men to take additional wives without the first wife’s consent. Sussan Tahmasebi, another founder of the campaign who was subsequently forbidden from leaving the country, recalls the movement’s accomplishments as significant. They gave voice to citizens who spoke boldly and fearlessly about women’s rights.

Another example of the weight of oppression Iranian women experience in their fight for emancipation occurred on December 27, 2017 on Enghelab (Revolution) Street, one of the busiest streets in Tehran. A woman lifted herself on top of a large utility box. Removing her white hijab, Viva Movahed, a 31-year-old mother, tied the head cover to a stick and waved it back and forth. A woman who witnessed this daring act did not wish to reveal her name to the press for security reasons, but commented that the scene made her feel both anxious and empowered. Since the incident, a protest movement called Girls of Revolution Street has spread throughout Iran. Images of women like Movahed have become symbols in other parts of the world by way of social media, including Masih Alinejad’s My Stealthy Freedom, a Facebook page in which women post pictures of themselves unveiled. Nasrin Sotoudeh, a female human-rights lawyer in Tehran, observes that women who protest on the streets and social media convey a simple message: women should be given the choice to decide whether to wear a hijab.

It is interesting to note that in 2011, Sotoudeh was arrested and sentenced to a six-year prison term for her defense of human rights activists. Newspapers reported that more than 35 women were violently attacked and arrested for demonstrating against the veil. One, Narges Hosseini, was sentenced to more than two years in prison. A statement from Tehran’s prosecutor general said such punishments came because the women were “encouraging moral corruption.”

Mahvash Sabet provides a final example of Iranian women’s perseverance and courage under the weight of oppression. In May 2008, Sabet and six other individuals were arrested in Tehran by intelligence agents from the Ministry of Intelligence and National Security. As members of the Bahá’í Faith, they did not receive the same protected status as Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians; official Iranian policy discriminates against Bahá’í citizens for their religious beliefs. In 1993, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Iran published Iranian Government Memorandum 1327. Drawn up by the Supreme Revolutionary Cultural Council and dated February 25, 1991, it had been marked CONFIDENTIAL and signed by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. The document addressed “the Bahá’í question” and outlined Iran’s policy of oppression toward Bahá’ís. The document stated that Bahá’í progress and development should be blocked by expelling adherents from universities, denying their employment, and enrolling them in schools meant to instill new religious ideology.

At first, Sabet and the six other Bahá’ís were sentenced to 20 years behind bars. Their sentence was later reduced to 10 years. In 2017, Sabet was released from prison after a decade in a 13-by-16-foot shared cell in Section 209 of Evin prison. In prison, she had endured false charges, threats, abuse, and humiliation, which, according to Sabet, must be endured in order to mitigate further charges and a longer prison term. Despite her long confinement, isolation, and constant abuse, Sabet willfully refused to submit or become a victim. Under caged brutality, she echoed activists past: she wrote poems.

Resistance, whether physical or through language and bearing witness to known truths, is a tradition as ancient as human life itself. One has seen it in the cold histories of the gulag, in the pernicious assaults on men and women in South Africa, and in the fight for civil rights in America. For while Iran may endure its own types of challenges, it is not alone in its challenges.

Activist women in Iran represent diverse backgrounds, education, religion, and economic statuses. They all yearn for greater freedom in relation to their legal rights, employment prospects, clothing, and movement. Insisting that they are the equal of any man, Iranian’s activist women are determined and strong in their demands for equal rights. Their unbroken movement toward attaining freedom is remarkable.

Since the 1979 revolution, Iranian women have been leaders in Iran’s nonviolent social and political reform—demanding freedom not only for themselves but also for their fellow citizens. They endure life under a repressive regime that controls them, segregates them, and refuses to grant them autonomy and equal opportunity. They are wrongly separated from their children, spouses, and families. They are harassed in public and private. They are unjustly arrested, falsely accused, and sentence without recourse. Once in prison, they are subjected to brutal treatment. Despite it all, Iranian women persist in openly voicing claims for self-determination. As they face subjugation and adversity, they adopt an attitude of refusal. They choose not to be victims, but reformers. Their fight is a moral movement that demands justice for women everywhere.

Recommended Resources

- Shirin Ebadi. 2016. Until We Are Free: My Fight for Human Rights in Iran. New York: Penguin Random House LLC. A personal account of the author’s struggle and courage as a lawyer defending women’s and children’s rights in Iran.

- Farzaneh Milani. 2011. Words Not Swords: Iranian Women Writers and the Freedom of Movement. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. An exploration of the history of the veil, gender segregation in Iran, and movements for desegregation.

- Valentine M. Moghadam. 2002. “Islamic Feminism and Its Discontents: Toward a Resolution of the Debate,” Signs 27(4). On Islamic feminism and the tensions between secular, religious, and expatriate Iranian feminists.

- Valentine M. Moghadam and Fatemeh Haghighatjoo. 2016. “Women and Political Leadership in an Authoritarian Context: A Case Study of the Sixth Parliament in the Islamic Republic of Iran,” Politics & Gender 12(1). Considers the political leadership of the small group of Iranian women elected to the Sixth parliament during the reform era, 2002.

- Afsaneh Najmabadi. 2000. “(Un)Veiling Feminism,” Social Context 18(3). Explores feminism within the context of Iranian society and reimagines an “Iranianness” that includes all, regardless of religion, language, ethnicity, and sexuality.

Professor Hoda Mahmoudi is the Bahá’í Chair for World Peace at the University of Maryland, College Park. She collaborates with a wide range of scholars, researchers, and practitioners to advance interdisciplinary examination and discourse on global peace. Her writings have appeared in leading publications, including Organizational Studies, International Review of Modern Sociology, and The Journal of Bahá’í Studies. Professor Mahmoudi serves as an advisory board member of the Iran 1400 Project.

-

Hoda Mahmoudihttps://iran1400.org/author/hoda-mahmoudi/