Layla Diba was the founding director of the Negarestan Museum, which housed collections of 18th and 19th century Iranian painting until the 1979 Revolution. In 2013 she curated an exhibition titled Iran Modern at New York’s Asia Society. The exhibition, as Diba noted, displayed how the invention of modernity in the context of Iranian art cannot be separated from the invention of tradition. Beyond that, pieces from the collection point to how modernity was not simply mandated from above but also emerged from below. This article attempts to bring these ideas into conversation with Professor Talinn Grigor’s article on the early Pahlavi Modernists and their establishment of the Society for National Heritage as well as Professor Hamid Keshmirshekan’s article on neo-traditionalism and the “Saqqa-khaneh” school of painting of the 1960s.

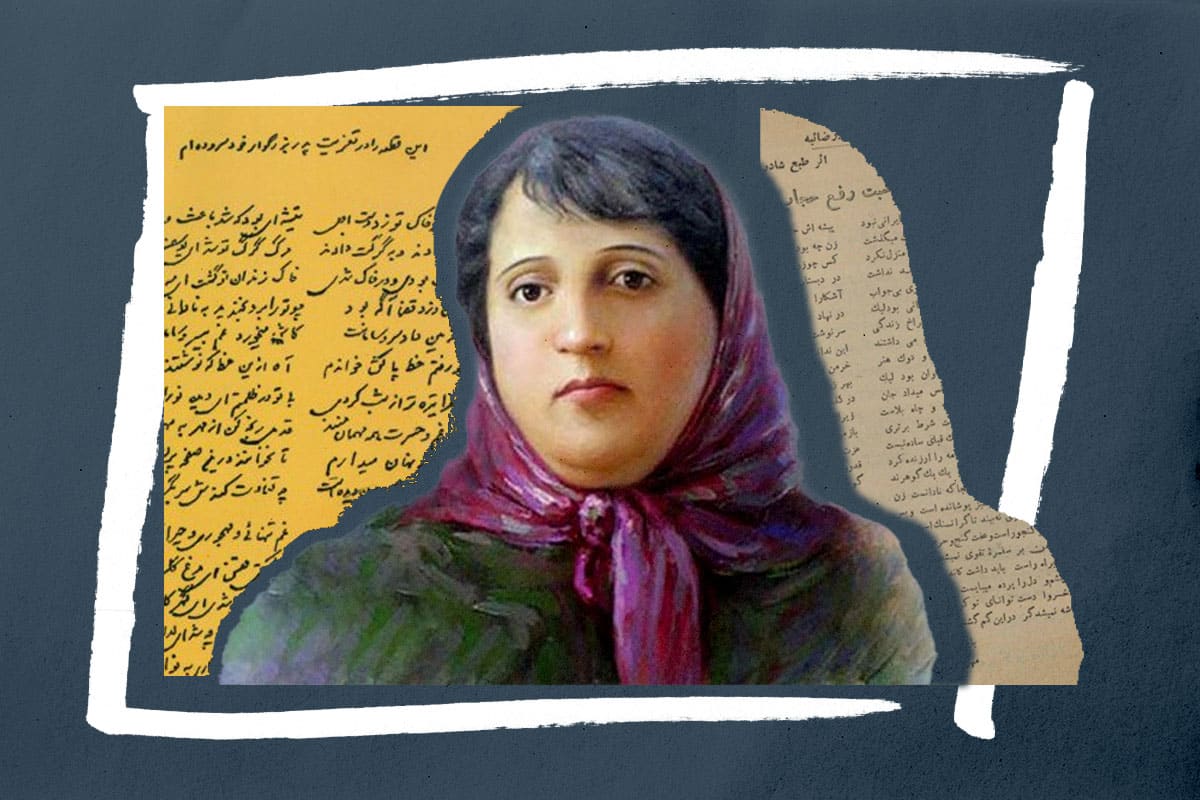

The terms “modernity” “modernization” and “modern” have all remained fluid in the contemporary history of Iran. This truth is also reflected in the art that has been produced in the country or in the Iranian diaspora over the past century. As Leyla Diba notes, the history of Iranian modern art is inextricably linked with Iran’s relationship with Great Britain, Russia and later the United States. However, one cannot deny that modern artists also found inspiration in their native surroundings. These dual sources of inspiration are illustrated by the differing styles of art produced in Iran during the Constitutional Period. Diba distinguishes between the arts produced in Tehran and Tabriz and those produced in Isfahan in those years. The Tehran and Tabriz schools embraced academic realism, which was imported from the academies of Europe and Russia. An example of this is the work of Kamal al-Molk, an Iranian who had studied the portraits of the great European artists like Rembrandt and Titian and employed similar techniques in his painting. Al-Molk also directed the Madreseh Mostazrafeh Sanaye, an art school in Tehran.

In contrast, during the same period, artists in Isfahan worked to revive the artistic legacy of the Safavid dynasty. Art in Isfahan revolved around the craftsmanship of workshops rather than around the discussions of artistic theories in academies and art schools. Leyla Diba notes that while there existed no public museums or archives at the time, historical imagery and knowledge were transmitted within the lines of family dynasties and through the rich and vibrant mosque and palace cultures still present in Isfahan. One of the key figures of the early revivalist movement in Isfahan was Mirza Agha Emami, a member of the Emami dynasty of painters, who established a workshop in Isfahan to train a new generation of artists there.

In 1925 Reza Shah Pahlavi gained the throne of Iran. His fierce and aggressive nationalism and his goals of modernization can be viewed in the sphere of art and culture. Nowhere is this more evident than in the establishment of the Anjoman-e Asar-e Melli, or the Society for National Heritage. Tallinn Grigor explains that the Society for National Heritage (SNH) allowed for some modernists during the early Pahlavi period to veil their political muscle in a cultural veneer. The SNH roots date back before 1925, as Grigor mentions, and its zeal for modernity was shaped during the Constitutional period and by groups like Iran-e Now (New Iran), a short-lived anti-clerical and fascist political party. The SNH viewed its mission as a civilizing one and was very much connected in the bureaucracy of the Pahlavi government, which shared with equal vigor its vision for modernity. SNH aimed to preserve and restore historical landmarks and honor the memory and glory of Iran. It is fascinating that a group of secular and elite intellectuals found it imperative to reclaim and revive the past in order to put Iran on a course of modernization. The ideas of Iranian unity and collective memory also played important roles in the politics of the Pahlavi period and more directly in the ideology of the SNH. This was evident in the most notable project of the SNH, the reconstruction of Ferdowsi’s mausoleum in Tus.

Reza Shah officially inaugurated the mausoleum in 1934. Dressed in a military uniform, the Shah remarked:

“Although by loving the poetry of the Shahnameh Iranians have made their hearts the resting-place of Ferdowsi, it was necessary to take some action and construct a structure and decorate it so that [the people could] also display their apparent appreciation. For this reason, we ordered full attention [be paid] to the construction of this historic monument.”

The mausoleum was built with pure and uncontaminated white stone and modelled after the tomb of Cyrus the Great at Pasargadae. Thus linking Ferdowsi to Cyrus the Great, the SNH attempted to invoke Iran’s Achaemenid past. The revival of “forgotten forms”, the SNH maintained, would reawaken the national spirit—producing, in essence, an Iranian renaissance. The term zawq, or artistic taste, was used in reference to the revival of such styles and contrasted with the dark and dying structures of the Qajar era. In fact, the SNH was influential in the destruction of Tehran’s Qajar city walls. The ideology and actions of the SNH prove show how modernity was in part mandated from above. They also demonstrate how the modernist discourse of the last century relied heavily upon ideas of historical revival.

Throughout the early decades of the Pahlavi period, the government’s political agenda influenced Iranian art. This became especially evident after the 1953 coup and into the 1960s, which is when art historian Hamid Keshmirshekan argues that state cultural policies were formalized, and art became a handmaiden to power. This means that art and architecture were very much influenced by the dominant discourses surrounding Iranian national identity. The Pahlavi government functioned as the main patron of the arts and therefore was extremely influential in the creation of a “national” school art, which relied heavily upon the attempt to express national identity in the modern language of art.

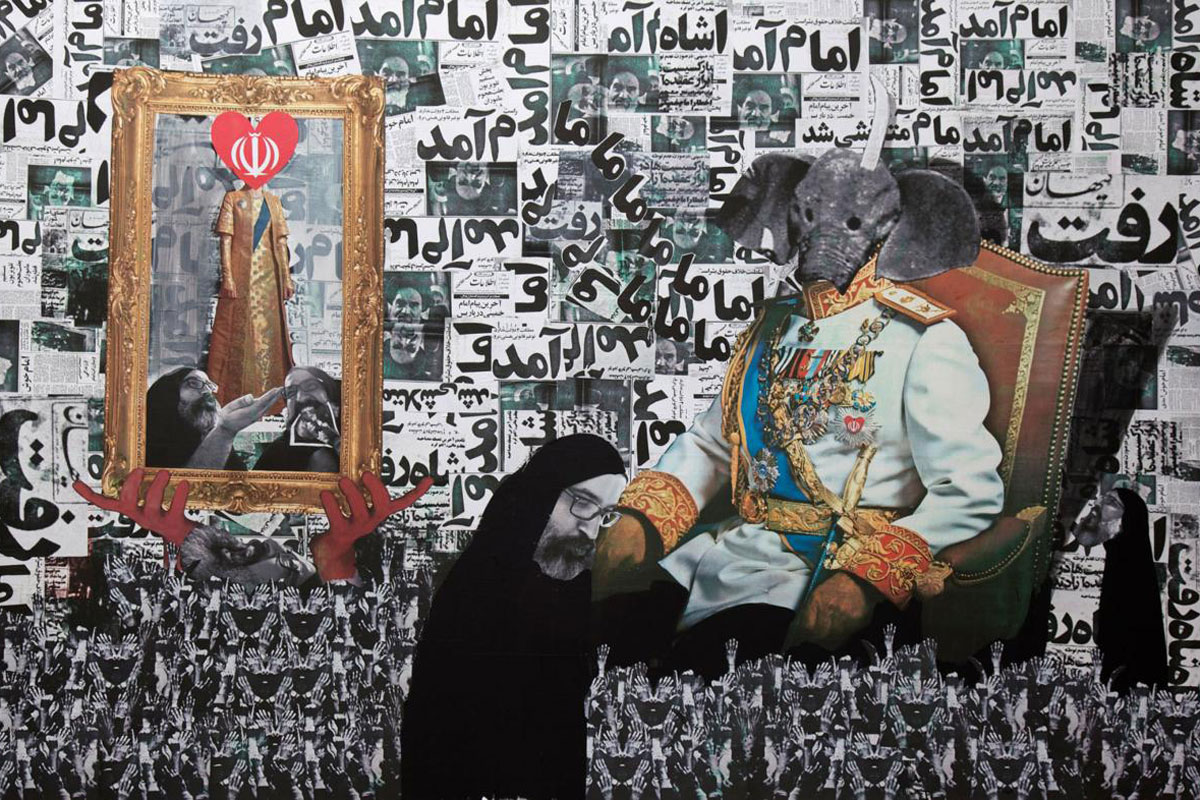

One of the artistic movements in this new Iranian national school of art was the Saqqa-Khaneh movement, which developed in the 1960s. At its core, the Saqqa-Khaneh was a neo-traditionalist movement, which sought to infuse the imagery of local crafts and symbols with the modern language of art. Saqqa-Khaneh, as Keshmirshekan notes, are votive foundations with charitable structures with fountains or water dispensers for public refreshment. They can be found throughout Iranian towns and cities. The term was first applied to art by a lecturer at the Tehran College of Decorative Arts, Karim Emami (no relation to the previously mentioned Mirza Agha Emami), and was meant to describe artistic pieces which referenced Shi’ite votive art. Over time it became applied to all forms of modern art which evoked traditional and decorative elements. Saqqa-khaneh painters worked independently, yet they were aware of each other’s art. Some like Charles Hossein Zenderoudi were inspired by Shi’ite shrines and assemblies and calligraphic inscriptions. Others like Sadeq Tabrizi were inspired by the symbolic articles found in traditional folk art.

This suggests the organic nature of the artistic movement, which existed without a clear creative hierarchy. It also points to the breadth of the movement, which Kamran Diva describes as a type of “Iranian pop art,” which looked at the inner beliefs and popular symbols of the Iranian people (as Pop Art looked at the symbols and tools of a mass consumer culture). Though artists themselves worked independently, their art depended heavily upon the largesse of the Pahlavi government. The Department of Fine Arts and Country hosted Tehran “biennials,” which were visited by members of both the domestic and international elite. Saqqa-khaneh became a sort of Iranian national school of painting which synthesized symbols of the past with modern styles and techniques. Here, again, is an example of how Iranian modern art attempted to revitalize and repurpose the past.

Layla Diba observes that Iranian modern art created the synthesis of both global and local. This synthesis can be seen in the contemporary art of Iran to this day. The development of the Tehran and Tabriz academies and workshops in Isfahan during the Constitutional period, the creation of the Society for National Heritage, and the emergence of the Saqqa-Khaneh movement further illustrate Diba’s thesis that “modern” in the context of Iranian art was both a product of influence from above and organic movements among artists.

Sources Consulted:

- The Formation of Modern Iranian Art FROM KAMAL-AL-MOLK TO ZENDEROUDI by Layla S. Diba

- Recultivating “Good Taste”: The Early Pahlavi Modernists and Their Society for National Heritage by Talinn Grigor

- Neo-Traditionalism and Modern Iranian Painting: The “Saqqa-khaneh” School in the 1960s by Hamid Keshmirshekan

Christian Petrillo is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania. He is particularly interested in the cultural and social history of Iran, especially in the cultural dialogues between Russia and Iran leading up to the Constitutional Revolution. He was the recipient of the University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages and Civilization Department's Best Essay Award in 2019 for his paper on Mirza Fatali Akhunzade and Cultural and Linguistic Resistance.

-

Christian Petrillohttps://iran1400.org/author/christian-petrillo/